A Brute by Any Other Name: The Tragedy of Fordicidia (Part I)

Abraham Lincoln and William Shakespeare

Well may it sort that this portentous figure

Comes armed through our watch; so like the king

That was and is the question of these wars.

-Hamlet 1.1

Harold Bloom famously declared "Shakespeare will go on explaining us, in part because he invented us." Many critics decry Bloom’s statement as the apex of Bardolatry, the excesses of a society so drunk on the poet and playwright that they’ve committed his memory to the mechane of apotheosis. In truth, I don’t think Bloom goes far enough.

The enzyme of modern consciousness was conjured by Shakespeare. His works catalyzed an intricate cascade of psychological and spiritual reactions, as mankind fermented with new forms of interiority. The characters and ideas that the bard loosened upon the earth altered us, in ways we can scarcely fathom. Our language is his.

Dante invented hell but Shakespeare fathered her inhabitants. When modern man thinks of the devil it is not the three-faced beast of the ninth circle, but the flesh and blood force of Iago or Gloucester. Even if they don’t recognize the names they know the forms. Romeo and Juliet burn in a million more minds than Paolo and Francesca. When a schoolboy thinks of Caesar he is meditating on Shakespeares rendition. How many men are convinced that the Romans's final words were “Et tu Brute?” The bard rummaged through history and dressed giants as his dolls. And somehow he left his playthings more noble than he found them. Falstaff is more real than Henry V. Japanese students may never hear the name King Lear, but they have seen his saga through Kurosawa’s samurai. Shakespeare is universal. Shakespeare is out of doors. And if we look at the dominance of the tongue he forged versus that of his Florentine counterpart, this universalism is all but vindicated.

But any man with half a brain is at least partially aware of the Bard’s part upon the creation of the English language, and they have probably heard a thing or two about his creation of literary interiority. But I am bold enough to say that these legacies are his most superficial.

Shakespeare is the circumference of our intellectual and creative possibilities. He contains us. He has us beat. But I find myself constantly returning to an even more terrifying conclusion, a conclusion that I can never seem to capture in words. Shakespeare seems to exert a demiurgic force upon our world. Like a flamboyant Ptah, the Bard spoke form into being. Frequently when I am investigating some mystery or historical happenstance, I discover his fingerprint, and it vexes me. Downard saw it in the Kennedy assassination. I see it in stranger places still. As amusing as the prospect of a shadowy cabal of Bard cultists is, I reckon the other possibility more grand and stupefying. The possibility that this half-god wrote the scripts that mankind would unconsciously play out for millennia to come. In early America, many a household owned just two books, the Bible and Shakespeare. They would be forgiven for thinking that both were penned by the same author.

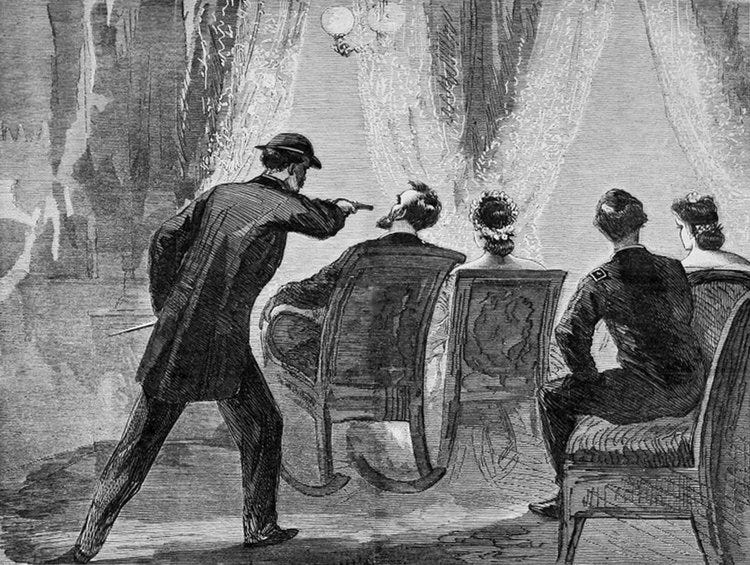

Shakespeare’s presence pulsed through early America. In the thoughts of her founders, on her stages, and in her literature. But this force fully manifested in Ford’s theater, a day after the ides of April in the spring of 1865.

It is widely acknowledged that the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was a national tragedy. What is less acknowledged, is that it bore all the hallmarks of a Shakespearean tragedy. Just as in the Bard’s plays, the characters were visited by ghosts, plagued by prophecies, and many of the supporting actors went mad. Abraham Lincoln adored Shakespeare, and his assassin was the country’s most adored Shakespearean actor. Most modern Americans are aware of this last detail, and yet I doubt they have properly digested it. To present a contemporary parallel, it would be as if Donald J Trump was gunned down during a screening of Killers of the Flower Moon, and the gunman revealed himself to be DiCaprio. But even this analogy fails to do the gravity of Ford’s Theater justice.

Thematically, the Tragedy of Ford’s theater seems to most mirror two of Shakespeares plays, Julius Caesar and Richard III. All three narratives involve assassination following a civil war. Julius Caesar after his war with Pompey, the War of the Roses in the case of Richard III, and with Lincoln that of the American Civil War. But most importantly, the protagonists of Ford’s Theater personally identified with the characters of the aforementioned Shakespearean Tragedies. And like all good tragedies, the characters’ families were linked in inexplicable ways.

John Wilkes Booth’s signature role was the same as his father’s before him, Richard III. It was the act he opened with and the act he was known for. Critics declared he was better at the role than anyone in the country, including his slightly more acclaimed brother, Edwin. The character of Richard was a perfect one to channel John's passionate and impulsive energies. But it was not his favorite part, nor did he particularly identify with the character. Instead, the role he most identified with was not his father’s signature role but his fathers’s namesake.

Shakespeare made great use of names with a prophetic intent, taking advantage of their linguistic and symbolic attributes which underpin a conception of the self and of predestination which are the stuff that prophecies, and not just dreams, are made of. Nomen erat omen. Names are omens: because I was given a particular name, I am doomed (or destined) to fulfill the fate traditionally associated with it. Names are not just signs, or omens, they can be agents, or prophets, προφητής, that is, they can “speak before,” as well as “speak forth,” as if to say: “my name speaks forth my destiny,” or “my name speaks for me before I do.” This does not mean to say, of course, that all names are successfully prophetic, that every “Caesar” will necessarily become a Caesar, only that names can be prophetic – indeed, they are intended to be so.

The legendary founder of the Roman Republic was Lucius Junius Brutus. He led the revolt to overthrow the tyrannical last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus. For the remainder of the Roman Republic, the name was synonymous with the overthrow of tyrants. Some five hundred years later, a descendant of his followed in his footsteps. On the ides of March 44 BC, Marcus Junius Brutus led the plot to assassinate his friend Caesar. In many ways, he was a victim of his own name. The year before the killing, public opinion was beginning to turn on Caesar, graffiti appeared glorifying Marcus’ ancestor Lucius, and chastizing Marcus for not living up to the reputation of his namesake. Would a Brute by any other name have struck so deep? The noble prestige that was once synonymous with Junius Brutus fractured, bifurcating across the march of history. This becomes apparent when you examine his two most famous literary incarnations. Dante Alighieri puts Marcus Junius Brutus in the lowest circle of hell. Shakespeares treatment is far more ambiguous. Shakespeares Brutus is noble, and depending on the reader and his background, Brutus could be seen as either the hero or the tragic villain of the Bard’s play.

And so how odd, that a Shakespearean actor by the name of Junius Brutus Booth, would give birth to the man who would play out his namesake’s violence.

John Wilkes Booth most certainly identified with his father’s namesake. And he had played out the murder of Caesar upon the stage to roaring applause hundreds of times. While Abe Lincoln did not see himself as a Caesar, John and the rest of the South certainly did. Southerners explicitly connected President Lincoln to Caesar, and their names became twinned in the bitter invectives of the men down in Dixie. It was widely believed that the Virginian motto “Sic Semper Tyrannis” (thus always to tyrants) originated from the lips of either Lucius Junius Brutus or his descendent, and so it is this phrase that John Wilkes Booth reportedly howled when the Hurly Burly was done. From Booth’s final diary entry: