Saint Callixtus of Rome was among the most charming and eccentric Popes of the third century. The first Bishop of Rome to have been a slave, and even stranger, almost all we know of the queer fellow comes from the writings of his arch nemesis, Hippolytus of Rome. And yet he was a man of tremendous guile and cunning, and if my theory is correct, an ingenious political operator.

(This post may go over the email limit so read it in substack)

Let’s first take a look at the only primary source we have of Callixtus’ life, written by his rival Hippolytus of Rome (traditionally recognized as the first anti pope) in Book IX of Refutation of all Heresies. What is important to remember is the need to view the ‘biography’ through a critical lens. There is much calumny and slander, but all slander has to be based on some level of truth to be convincing. Our challenge is separating the fact from the fiction. Let us first engage with the unedited text that Hippolytus wrote before we attempt to contextualize it.

“Callistus happened to be a domestic of one Carpophorus, a man of the faith belonging to the household of Caesar. To this Callistus, as being of the faith, Carpophorus committed no inconsiderable amount of money, and directed him to bring in profitable returns from the banking business. And he, receiving the money, tried (the experiment of) a bank in what is called the Piscina Publica. And in process of time were entrusted to him not a few deposits by widows and brethren, under the ostensive cause of lodging their money with Carpophorus. Callistus, however, made away with all (the moneys committed to him), and became involved in pecuniary difficulties. And after having practised such conduct as this, there was not wanting one to tell Carpophorus, and the latter stated that he would require an account from him. Callistus, perceiving these things, and suspecting danger from his master, escaped away by stealth, directing his flight towards the sea. And finding a vessel in Portus ready for a voyage, he went on board, intending to sail wherever she happened to be bound for. But not even in this way could he avoid detection, for there was not wanting one who conveyed to Carpophorus intelligence of what had taken place. But Carpophorus, in accordance with the information he had received, at once repaired to the harbour (Portus), and made an effort to hurry into the vessel after Callistus. The boat, however, was anchored in the middle of the harbour; and as the ferryman was slow in his movements, Callistus, who was in the ship, had time to descry his master at a distance. And knowing that himself would be inevitably captured, he became reckless of life; and, considering his affairs to be in a desperate condition, he proceeded to cast himself into the sea. But the sailors leaped into boats and drew him out, unwilling to come, while those on shore were raising a loud cry. And thus Callistus was handed over to his master, and brought to Rome, and his master lodged him in the Pistrinum.

But as time wore on, as happens to take place in such cases, brethren repaired to Carpophorus, and entreated him that he would release the fugitive serf from punishment, on the plea of their alleging that Callistus acknowledged himself to have money lying to his credit with certain persons. But Carpophorus, as a devout man, said he was indifferent regarding his own property, but that he felt a concern for the deposits; for many shed tears as they remarked to him, that they had committed what they had entrusted to Callistus, under the ostensive cause of lodging the money with himself. And Carpophorus yielded to their persuasions, and gave directions for the liberation of Callistus. The latter, however, having nothing to pay, and not being able again to abscond, from the fact of his being watched, planned an artifice by which he hoped to meet death. Now, pretending that he was repairing as it were to his creditors, he hurried on their Sabbath day to the synagogue of the Jews, who were congregated, and took his stand, and created a disturbance among them. They, however, being disturbed by him, offered him insult, and inflicted blows upon him, and dragged him before Fuscianus, who was prefect of the city. And (on being asked the cause of such treatment), they replied in the following terms: Romans have conceded to us the privilege of publicly reading those laws of ours that have been handed down from our fathers. This person, however, by coming into (our place of worship), prevented (us so doing), by creating a disturbance among us, alleging that he is a Christian. And Fuscianus happens at the time to be on the judgment-seat; and on intimating his indignation against Callistus, on account of the statements made by the Jews, there was not wanting one to go and acquaint Carpophorus concerning these transactions. And he, hastening to the judgment-seat of the prefect, exclaimed, I implore of you, my lord Fuscianus, do not believethis fellow; for he is not a Christian, but seeks occasion of death, having made away with a quantity of my money, as I shall prove.The Jews, however, supposing that this was a stratagem, as if Carpophorus were seeking under this pretext to liberate Callistus, with the greater enmity clamoured against him in presence of the prefect. Fuscianus, however, was swayed by these Jews, and having scourged Callistus, he gave him to be sent to a mine in Sardinia.

But after a time, there being in that place other martyrs, Marcia, a concubine of Commodus, who was a God-loving female, and desirous of performing some good work, invited into her presence the blessed Victor, who was at that time a bishop of the Church, and inquired of him what martyrs were in Sardinia. And he delivered to her the names of all, but did not give the name of Callistus, knowing the acts he had ventured upon. Marcia, obtaining her request from Commodus, hands the letter of emancipation to Hyacinthus, a certain eunuch, rather advanced in life. And he, on receiving it, sailed away into Sardinia, and having delivered the letterto the person who at that time was governor of the territory, he succeeded in having the martyrs released, with the exception of Callistus. But Callistus himself, dropping on his knees, and weeping, entreated that he likewise might obtain a release. Hyacinthus, therefore, overcome by the captive's importunity, requests the governor to grant a release, alleging that permission had been given to himself from Marcia (to liberate Callistus), and that he would make arrangements that there should be no risk in this to him. Now (the governor) was persuaded, and liberated Callistus also. And when the latter arrived at Rome, Victor was very much grieved at what had taken place; but since he was a compassionate man, he took no action in the matter. Guarding, however, against the reproach (uttered) by many — for the attempts made by this Callistus were not distant occurrences — and because Carpophorus also still continued adverse, Victor sends Callistus to take up his abode in Antium, having settled on him a certain monthly allowance for food. And after Victor's death, Zephyrinus, having had Callistus as a fellow-worker in the management of his clergy, paid him respect to his own damage; and transferring this person from Antium, appointed him over the cemetery.” (Chapter 7, Book IX of Refutation of all Heresies)

“Callistus attempted to confirm this heresy — a man cunning in wickedness, and subtle where deceit was concerned, (and) who was impelled by restless ambition to mount the episcopal throne. Now this man moulded to his purpose Pope Zephyrinus, an ignorant and illiterate individual, and one unskilled in ecclesiastical definitions. And inasmuch as Zephyrinus was accessible to bribes, and covetous, Callistus, by luring him through presents, and by illicit demands, was enabled to seduce him into whatever course of action he pleased. And so it was that Callistus succeeded in inducing Zephyrinus to create continually disturbances among the brethren, while he himself took care subsequently, by knavish words, to attach both factions in good-will to himself. And, at one time, to those who entertained true opinions, he would in private allege that they held similar doctrines (with himself), and thus make them his dupes; while at another time he would act similarly towards those (who embraced) the tenets of Sabellius.” - (Chapter 6, Book IX of Refutation of all Heresies)

So our friend Callixtus was a slave under the command of a Christian by the name of Carpophorus. His master had set him in charge of large sums of money with the intention of forming a kind of banking system known as the Piscina Publica. Callixtus loses the money, and Hippolytus of course blames this on his own poor conduct. We cannot truly know if Callixtus was at fault. From here, the young Greek in fear of his masters retaliation escapes aboard a vessel preparing to sail. This dramatic scene ensues as Carpophorus calls out to the ship to return, upon which Cal desperatly attempts suicide in the waters below. Again, lets view this critically, it is far more likely that Cal was simply trying to escape then trying to end his life. Cal is then entrusted with trying to regain some of the capital he has lost by locating those parties that owed him. He approaches a group of Jews at the synagogue on the day of the Sabbath. The group of Jews then assault him and bring him to the local prefect for disturbing the sabbath. Now Hippolytus tries to frame this as Cal’s second suicide attempt, as if he simply ran head first into the synagogue hoping to be beaten to death. This of course makes no sense, as their are far easier methods of suicide than being beaten over the head with a menorah. It is far more likely that the group of Jews did indeed owe him money (ironically). Nevertheless, there is something almost charming about Hippolytus’ commitment to framing Callixtus as a suicidal maniac.

The prefect sends Callixtus as punishment to a mine in Sardinia, a terrible fate indeed. A certain concubine of the emperor Commudus, Marcia, was a Christian, and looking to carry out a charitable act acquired a list of the Christian Martyrs in Sardinia. Hippolytus claims that Callixtus was not on that list, but that he begged the agent sent by Marcia to free himself as well. Again and again throughout the narrative Hippolytus tries stressing that Callixtus was not in fact a Christian. However, the context makes it quite obvious that he was. Why on earth would Marcia and her agent simply allow the manumission of Callixtus if he was not a Christian?

Hippolytus’ denial of Callixtus’ past status as a Christian is integral to the slanderous narrative he develops for several reasons. For one, if Callixtus was a Christian while a slave of Carpophorus who was also a Christian, it would reflect very poorly on his master in his treatment of Cal. This would lead one to doubt how much of Cals “monetary incompetence” was actually the fault of Cal. Suicide as a Christian is also a mortal sin, and would have been far more frowned upon then it would have been if one were a pagan. So his Christianity would have poked major holes in the suicidal maniac narrative. And yet the fact that Marcia has Cal released as a Christian, and then Pope Viktor gave him a monthly allowance afterwards is strong evidence that Cal was indeed a Christian before his emancipation.

(short and humorous interjection. I first found out about Mr. Cal due to a summer seminar I had three years ago with a visiting professor from the American heartland, who was also an openly gay Catholic. Go figure. What was interesting is that he seemed to favor Hippolytus’ narrative, as it framed Cal as this flamboyant, melodramatic, and masochistic theater kid.)

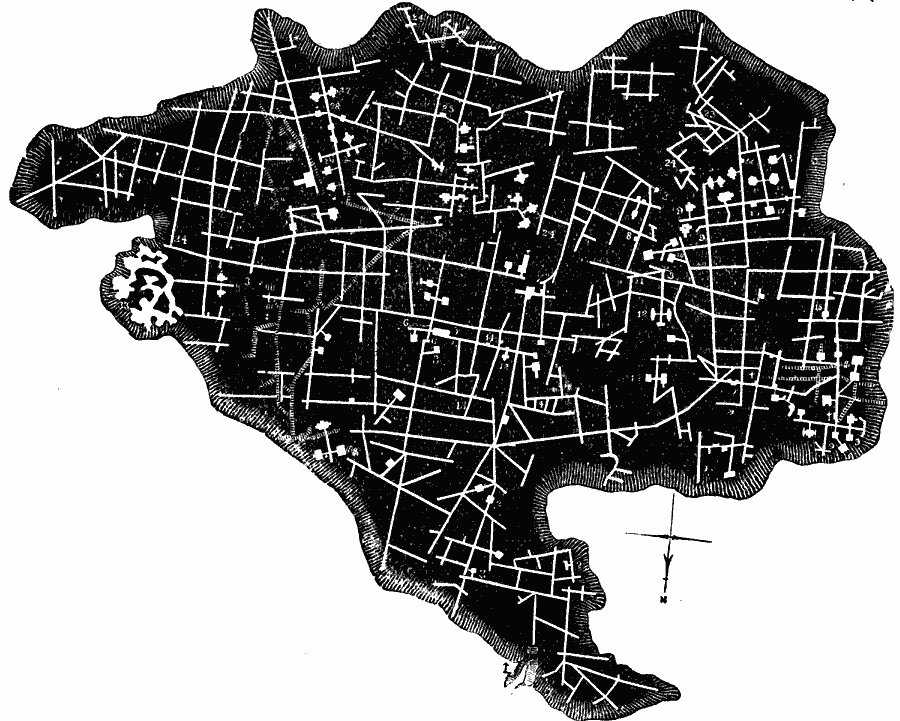

Now after Callixtus is given a kind of pension from Pope Victor, he has a rapid rise all the way to the highest Christian office in Rome. He is made a deacon and then placed in charge of the cemeteries. Now, when we talk of cemeteries today it truly does not due justice to the sprawling catacomb complexes of the early Roman Christians. This position was not that of a lowly undertaker, but the foreman of an incredibly complex subterranean construction project.

The largest of the Roman catacombs, and the one that now bears Cals name, the Catacombs of Callixtus, had five different levels, running around 20 kilometers, and housed at its height 500k bodies. To be put in charge of such a project was no small thing.

Callixtus goes on to become a close confidant of Pope Zephyrinus, and upon Zeph’s death he is made Bishop of Rome. This is much to the ire of Hippolytus, who believed himself to have been robbed, thus sparking his SEETHE and the slanderous narrative that he would publish. (Hippolytus is traditionally considered to be the first antipope).

But here is what is truly interesting. Hippolytus maintains that the only way Cal became Pope is through simony and guile, by bribing and seducing the “simple” Zephyrinus into earning his favor. Now its easy to dismiss this as pure calumny, BUT, as we have seen, all slander is based in some fact. How could Hippolytus get away with claiming Cal used bribery to obtain his position if it wasn’t widely known that Cal had the money to do so? How could he claim that Calixtus’ “seduced” Zeph if he didn’t have a reputation as a deft political operator?

BUT WAIT? How could a former slave who was so destitute that he had to be given a charitable pension by Pope Zephyrinus’ predecessor, Pope Victor, have managed to amass enough money in such a short period of time to reasonably be accused of using bribery to gain influence? Now we are getting to what I find so interesting, something wholly ignored by scholars.

Before we even engage with this question, some background is needed.

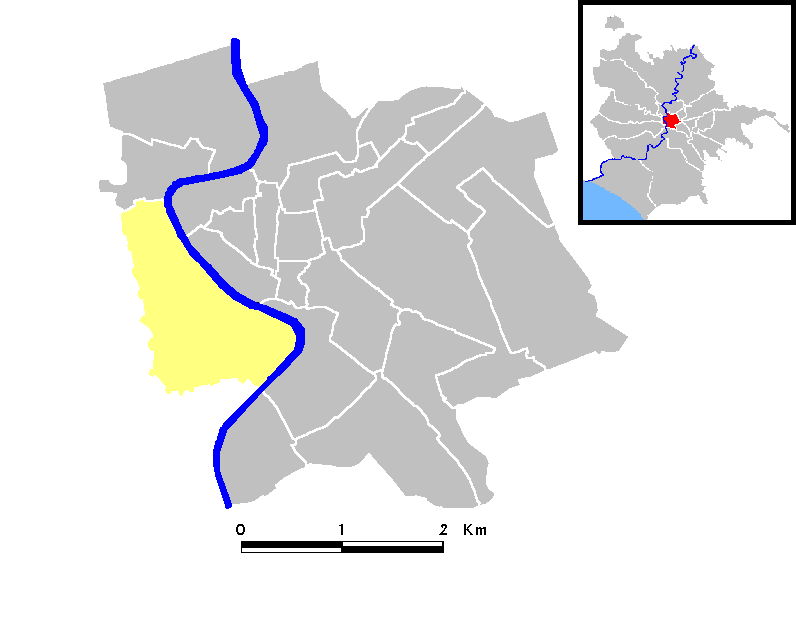

The 13th rione of Rome, Trastevere, was historically the fulcrum of Jewish identity in Rome (before the ghettoization). The name comes from the latin “trans Tiberim,” literally “across the tiber.” The area was not incorporated in the city of Rome de jure until the time of Caesar Augustus, and was historically an area for immigrants, mainly Jews and Syrians. In the Republican period, non citizens could not live within the cities de jure limits, and so the jews found themselves in this particular area. And so it is no wonder that the epicenter of the early Christian movement in Rome found itself in Trastevere.

So Trastevere can best be contextualized as the nucleus of early Christianity in Rome. Let’s take a look at a map real quick.

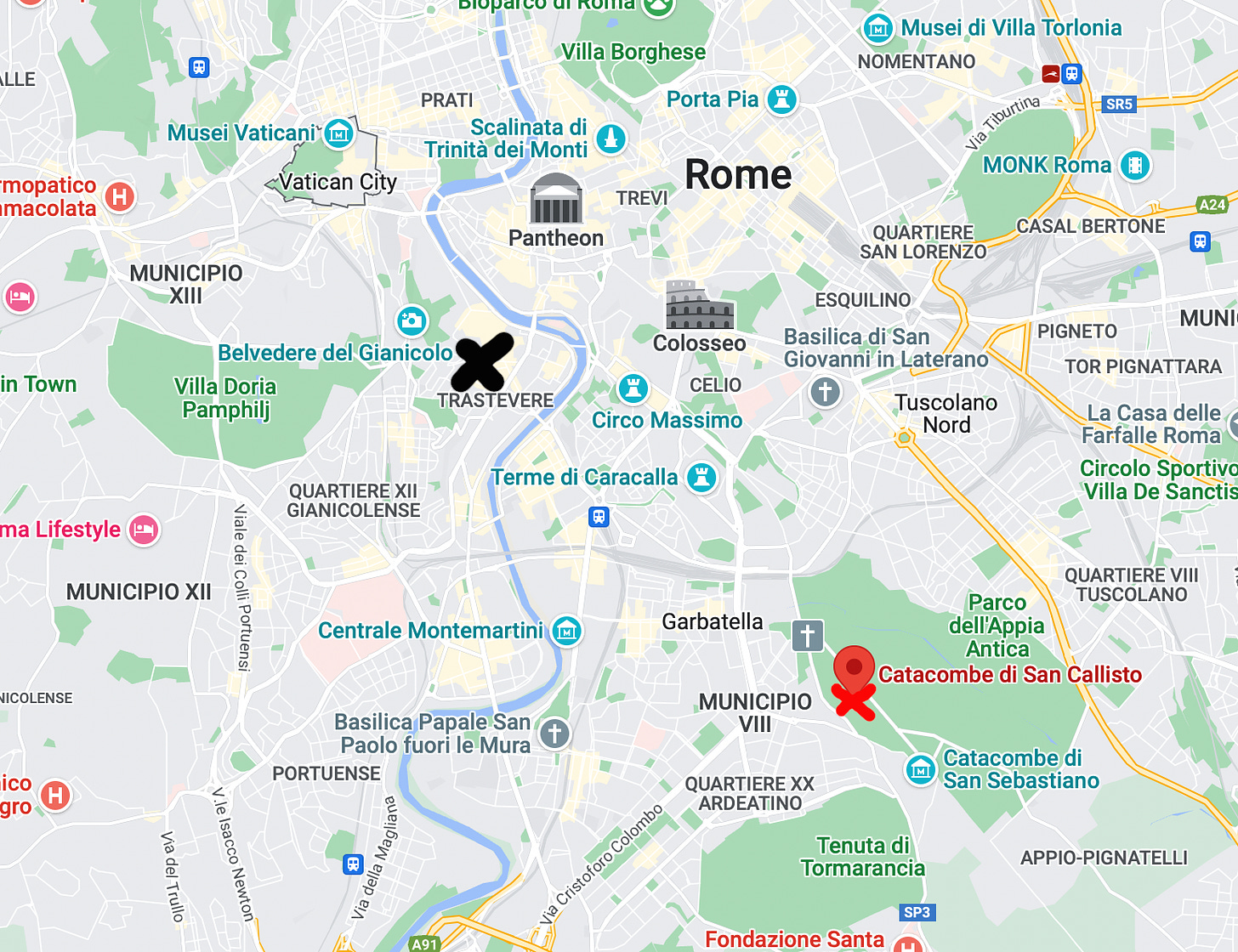

The black X is Trastevere, and the red X the catacombs of Callixtus and the general location of most of the Appian catacombs. The catacombs were the first landed property that the church ever owned. It is difficult to stress just how important the catacombs were to early Christianity. Julian the Apostate claimed, “Christians have gained most popularity because of their charity to strangers and because of their care for the burial of their dead.” Okay the point I am making with the graph is to show the great distance between Callixtus’ area of operations and the power center of 3rd century Christianity in Rome.

Now let’s discuss two churches in Trastevere. Santa Maria in Trastevere (one of the most important basilicas period) and the Basilica of San Callisto.

(Near email limit so those reading will have to continue on the actual substack website).

Both these churches are strongly linked to St Callixtus, with one building bearing his name and containing the well he was martyred in, and the other containing his relics.

Map of the two:

As you can see they are both right next to each other. And both churches are thought to be built over Saint Callixtus’ Domus. What do I mean by this? Many basilicas in Rome are built over the old house churches of important saints. Saint Callixtus’ had a sprawling house complex that used to comprise the area now containing the two churches. So not only did Callixtus have a massive house complex, but his house complex was in Trastevere, far from his base of operations near the Via Appia.

What is going on here? How did a former slave with near no money to his name, operating as a grave digger in the Appian way, amass a fortune and a power base in Trastevere, so much so that he ended up becoming Bishop of Rome?

Here is my theory. You must look at ancient Roman politics in the same way one would look at modern local politicking and mafia esque protection/favor winning.

The Christians may have been based in Trastevere, but where did every Christian have to go when burying their dead? And more then that, who had full control over the burial of the dead? Callixtus could have maneuvered and amassed favors with grieving families, giving preferential burial treatment for either bribes or favors. He could have amassed tremendous political capital with the Christians based in Trastevere, simply by virtue of the power he held over burials. (Not to mention actual financial capital lol). Once he became popular and influential enough with community, he could have convinced them to pool their resources so he could invest in the Domus that used to stand in the area. (A somewhat common practice). And from there, the deacon would have amassed enough influence and power to succeed Zephyrinus as Bishop of Rome.

There is much more that can be said about this remarkable figure, we haven’t even touched on his theological disputes, and the importance they had on ecclesiology. Or his dramatic martyrdom. We will continue with St Callixtus some other time.