There and at that moment I should have seen the City. I stood up on the bank and shaded my eyes, straining to catch the dome at least in the sunlight; but I could not, for Rome was hidden by the low Sabinian hills.

Soracte I saw there--Soracte, of which I had read as a boy. It stood up like an acropolis, but it was a citadel for no city. It stood alone, like that soul which once haunted its recesses and prophesied the conquering advent of the northern kings. I saw the fields where the tribes had lived that were the first enemies of the imperfect state, before it gave its name to the fortunes of the Latin race.

Dark Etruria lay behind me, forgotten in the backward of my march: a furnace and a riddle out of which religion came to the Romans--a place that has left no language.

-Hilaire Belloc

On certain late summer nights, on the cusp of dusk, when the air begins to cool and the city’s skin shimmers cobalt, I find my thoughts and spirit drifting north. There are certain squares built on ancient hills, elevated above the sediment and city sprawl, which grant a glimpse beyond the columns and cathedrals. And from the midst of Rome’s congested flesh, you can make out those silhouettes cut in the distance. At times their outline is nearly invisible, their shadow-spun countenance melting seamlessly into the sea of night, giant fallen phantoms, dead gods fading on the horizon. A perennial reminder to any Roman who dares forget that there are forces older than the forum.

I speak of those mountains lurking on the threshold, over the mantle of civilization. When seen from the city, their peaks induce a feverish vertigo. A break in your bearings, a rupture in the comfortable dimensions of urban life, pierced by an unbearable verticality. And those mountains hum. A chorus of deep whispers, drowned out by the brittle chatter of the piazza, only perceptible in moments of silence.

The lands north of Rome are scarred by strange magic. The land of Etruria, or what is left of it. A place where the fingerprints of forgotten gods are seared into the soil’s toponymy and topography. In certain villages, their ethereal influence is perceptible in the flesh of the native stock, warping faces into physiognomies otherwise long forgotten. An ancient force still reigns in that land. A tributary of effulgences, echoes of the past building momentum, unconscious wills and energies, from powers no longer truly acknowledged. But the names are still spoken. In the cities and streets, on maps and in dreams.

The Etruscans were religious to a degree that modern man cannot fathom. Their metaphysical orientation was so alien, so exotic, that it is difficult to even conceptualize, to put to words. To understand this lost race, you must first understand their gods. Those strange beings who reigned over Etruria. Only then can you look upon the mountains outside of Rome with the terror and awe of an Etruscan.

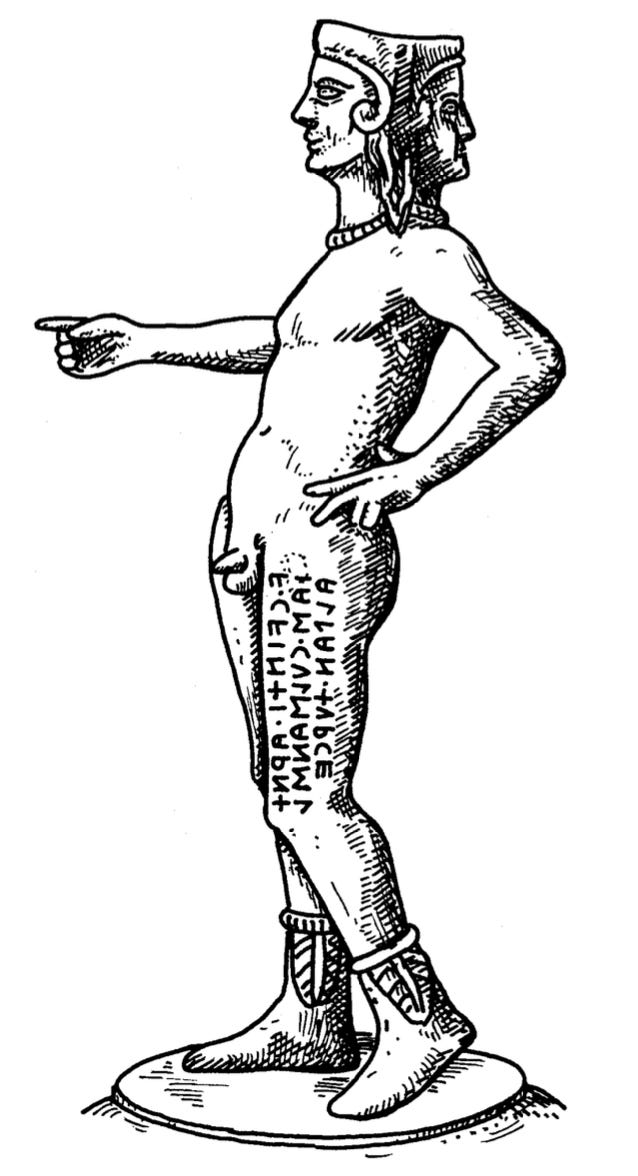

In the Etruscan mind, all natural phenomena was an expression of divine volition, and therefore reality was a matrix of signs to be deciphered. Etruscan religiosity was primarily a matter of deciphering providence in its earthly manifestations. Their religious texts resembled an encyclopedia of divination, an oracular handbook for contextualizing natural phenomena in their proper spiritual plane. The Etruscan’s reputation as soothsayers was famous throughout the Mediterranean, with Romans sending their sons to Etruria for a proper religious education.

“Writing defined and fixed the established channels of communication between gods and mortals. In a way, the signs of the gods were themselves a kind of writing that had to be deciphered by men. After the 1985 exhibit on Etruscan texts at Perugia, Scrivere Etrusco, Massimo Pallottino remarked that we could well call the Etruscans, like the Hebrews, the ‘‘People of the Book.’’ When Livy tells us that the Romans used to send their children to Etruria to learn letters in the fourth century bce, as they later used to send them to Athens, we can assume that it was the children of aristocrats, the Roman oligarchy, who needed to learn the art of divination as part of their training, to be able to lead armies in the field and carry out religious rituals in peace. With the study of the Etruscan books of divination they received a technical training that might have been the ancient equivalent of going to MIT to study engineering.”

(The Religion of the Etruscans- Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon)

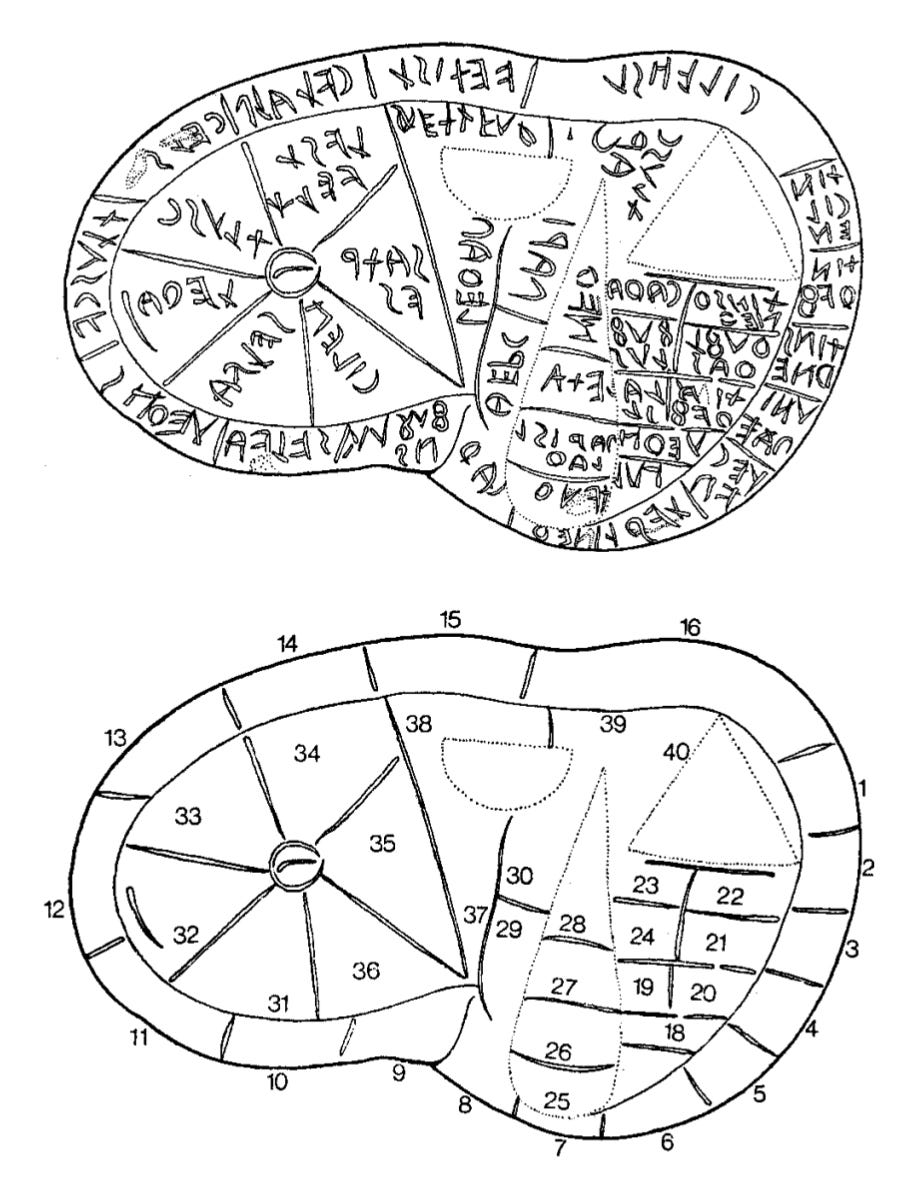

The riddle of Etruscan religiosity can be best glimpsed in the Liver of Piacenza, which I have discussed extensively in the past.

“Another very strange object also contains the names (abbreviated, but recognizable) of divinities who received cult. This is the life-sized bronze model of a sheep’s liver from northern Italy, near Piacenza, made around 100 bce. It may have been used by a priest in the Roman army. (Other ritual inscriptions are from an earlier period.)

The model was clearly used as a device to teach (or remind) Etruscan priests of the divinatory practice of reading the entrails of animals. As Nancy de Grummond discusses below priests or seers are shown using it in Etruscan art, including representations on several mirrors. According to the place where the liver of a sacrificed animal showed some special mark, the priest could guess the future or even bend it to his will. The Etruscans were particularly skilled in this haruspicina, or science of reading omens, and the Romans respected, hired, and imitated them. The sections of the liver correspond to the sections of the sky that were under the protection of each of the gods. There was a mystic correlation between the parts of a sacred area, like the sky, and the surface of the liver of a ritually sacrificed animal. Such a correlation allowed those who had mastered the technique to ‘‘read,’’ as it were, the god’s writing in the sky.

Each of the forty-two sections of the liver contains the names of one or more gods; there are fifty-one names, but several are mentioned two or three times. The sixteen sections in the margin of the upper (visceral) side correspond to the sixteen regions of the heavens, according to Martianus Capella (fifth-century ce). Further, a number of names of divinities on the liver appear in the description of the skies by Martianus.

The lower (venal) side of the liver has two names: Usil, the name of the Sun god, and Tivr, the Moon. A number of the names of these gods are familiar from various sources: Tin (Tinia), Uni, Hercle, Cath (Cautha/Kavtha), Usil, and Tivr. Others may represent epithets of gods. The placement of the different clusters of divinities indicates their function: so, for example, the right lobe contains the gods of heaven and lights (Tin, Uni, Cath, Fufluns); the god of water Nethuns (Neptune, whose name appears so frequently on the mummy wrappings); and Cilens, perhaps a god of Fate. finds that this constellation of divinities came together in the fourth century bce and that about half of the approximately twenty-eight different names of gods inscribed on the liver are of Etruscan origin. The other half came into Etruria from the surrounding Italic world, Umbria, and the area of Rome (Uni, Neth, and other deities).”

In the ritual space, the liver of the sacrificed animal became a microcosm for the heavens, and the Etruscans had damn near scientific precision in the procedures for interpretation. But this mystic sympathy extended far past haruspicy, with all of Etruria becoming a divine grid, a chessboard of telluric energy. The Etruscans placed a religious emphasis on boundaries, on the physical demarcation of space, in the same way they did with the liver. Boundaries given by divine mandate, which man were expected to reinforce and reforge through a process of theandric toil.

“Complex as the Piacenza liver and the descriptions of the regions of the sky are, these testimonia stand out as examples of an Etruscan belief system about spaces and boundaries that are the key for our understanding of much of the Etruscan worldview. What they both illustrate is an absolute need for defining spaces as contiguous entities, related to each other by a common border, but also separate from each other because of the very same border and because of the deity in charge of each space. Regardless of the nature of each specific space, each gains its identity and strength by being part of a pattern, a design of molecules, with infinite possibilities for expansion.

Furthermore, these contiguous spaces, as indicated on the liver and in the sixteen regions, not only extended horizontally on earth or in heaven but provided vertical links between heaven and earth, and between earth and the Underworld. In heaven the orientation of the regions was guided by the spatial directions: north, south, east, and west. On earth, these celestial spaces corresponded with a variety of spaces: first, the delimited, inaugurated spaces, templum or auguraculum, from which the sky was observed; second, the temenos, or enclosed space around a sanctuary, including features such as altars and temples; and third, features in nature such as mountaintops, rivers, lakes, and groves. As shown by the texts that describe the taking of auspices from such areas on earth, the orientation of their layout and the direction from which the celestial signs arrived were all tied to the division of the skies into the sixteen regions. The most famous of these instances is the contest between Romulus and Remus for the right to become the sole founder of Rome, but, as Cicero points out, this tradition was rooted in Etruscan principles.”

Etruria was a microcosm for both the celestial and chthonic worlds, with each patch of land being under the domain of a different god, or gods. Gods who were active in the world.

“While boundaries serve to separate spaces, they also invite the crossing over from one space to another. Such a crossing between the celestial space and the space on earth was defined in the Latin term of religio,* or binding, which is another way of marking a contiguous vertical boundary or ‘‘tie’’ between heaven and earth. The link between above and below provided strength and security, and a focal point, in Eliade’s terminology, an axis mundi, which served as a cornerstone for the stable world, for cosmos.

The interaction between heaven and earth required a language of communication. Mountaintops, such as those of Mount Soracte and Monte Falterona, provided a sense of proximity to the skies, and the ancient texts indicate that the language of interaction was usually dramatic. Depending on their role and the circumstances of their intervention, the deities in the skies would communicate with the humans on earth by signs such as thunder and lightning.”

Mount Soracte. A thematic tributary where all my interests seem to pool.

An obsession.

I briefly discussed that mountain, and the deity who was said to reign there, in my article on the Apollo of Veii. We will return to Soracte and Suri later.

Anyone familiar with my work will immediately understand my affinity for this people. The Etruscan mindset— their religious disposition— is so viscerally appealing to me. The mystic sympathy between matter and the divine, the omens, the enchantment, the absolute obsession with religious demarcation—truly I can say— in this lost race I find something of myself.

La campagna exists in a liminal space in relation to the church. Christianity spread in cities. The clerical authorities always found the countryside to be a bit of a problem. Regardless of which country, be it Italy or Ireland, the provincial folk tended to retain a pagan flavor. Latin America today is as good an example as any, with its litany of folk saints who exist outside of the Church. The old gods survive in Etruria, and their presence is palpable.

The idea that ancient religious practices can survive through folklore and folk magic is somewhat frowned upon in modern academia. And so I propose we search for a scholar who predated the pretensions and anxieties of the modern academic industrial complex. Charles Godfrey Leland is just the man for the job. Mr Leland was a scholar of a different age, a man with an adventurous spirit and a Fortean flair, a Folklorist with an appetite for magic. He wrote a peculiar book on the folk magic of Romagna. From the introduction:

Among these people, stregeria, or witchcraft--or, as I have heard it called, "la vecchia religione" (or "the old religion")--exists to a degree which would even astonish many Italians. This stregeria, or old religion, is something more than a sorcery, and something less than a faith. It consists in remains of a mythology of spirits, the principal of whom preserve the names and attributes of the old Etruscan gods, such as Tinia, or Jupiter, Faflon, or Bacchus, and Teramo (in Etruscan Turms), or Mercury. With these there still exist, in a few memories, the most ancient Roman rural deities, such as Silvanus, Palus, Pan, and the Fauns. To all of these invocations or prayers in rude metrical form are still addressed, or are at least preserved, and there are many stories current regarding them. All of these names, with their attributes, descriptions of spirits or gods, invocations and legends, will be found in this work.

Closely allied to the belief in these old deities, is a vast mass of curious tradition, such as that there is a spirit of every element or thing created, as for instance of every plant and mineral, and a guardian or leading spirit of all animals; or, as in the case of silkworms, two--one good and one evil. Also that sorcerers and witches are sometimes born again in their descendants; that all kinds of goblins, brownies, red-caps and three-inch mannikins, haunt forests, rocks, ruined towers, firesides and kitchens, or cellars, where they alternately madden or delight the maids--in short, all of that quaint company of familiar spirits which are boldly claimed as being of Northern birth by German archæologists, but which investigation indicates to have been thoroughly at home in Italy while Rome was as yet young, or, it may be, unbuilt. Whether this "lore" be Teutonic or Italian, or due to a common Aryan or Asian origin, or whether, as the new school teaches, it "growed" of itself, like Topsy, spontaneously and sporadically everywhere, I will not pretend to determine; suffice to say that I shall be satisfied should my collection prove to be of any value to those who take it on themselves to settle the higher question.

Connected in turn with these beliefs in folletti, or minor spirits, and their attendant observances and traditions, are vast numbers of magical cures with appropriate incantations, spells, and ceremonies, to attract love, to remove all evil influences or bring certain things to pass; to win in gaming, to evoke spirits, to insure good crops or a traveller's happy return, and to effect divination or deviltry in many curious ways--all being ancient, as shown by allusions in classical writers to whom these spells were known. And I believe that in some cases what I have gathered and given will possibly be found to supply much that is missing in earlier authors--sit verbo venia.