“Understand this well: there is something holy, something divine, hidden in the most ordinary situations, and it is up to each one of you to discover it.” - St Escriva

My primary interest, both aesthetically and historically, is the imposition of the miraculous within the banal confines of daily life. As stated in a previous article of mine, “Only a short time ago, the miraculous was seen as another facet of daily life. The personal diaries and public records of our collective historical heritage are rife with vivid and corroborated accounts of the seemingly impossible. Apparitions, inexplicable healings, from the banal to the bizarre. These are all willfully ignored by the methods of modern historiography, rationalized away as “mass psychosis” or some other quasi-Freudian psychological sleight of hand. The retroactive ‘mass psychosis’ diagnosis is just as unfounded and mystical as 'divine intervention.' Framing your explanation through the lens of 'psychology' doesn't add validity to it or make it more objective. But history must be neat, and wholly compatible with the secular ontology of our contemporary high priesthood.”

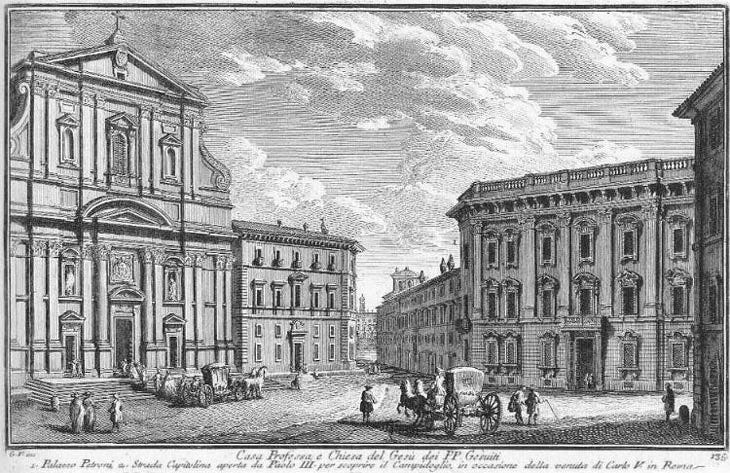

I find great joy in scouring the historical records for primary sources that recount the unexplainable phenomena that manifest alongside the daily humdrum of existence. In no area or location is this more dramatic than Baroque Rome. In the 16th and 17th century, the city of Rome was transformed into a stage, rife with carefully coordinated religious rituals and outpourings of dramatic showmanship from both the nobility and the plebeians alike. Each piazza became a tightly controlled spectacle, full of color and pomp- piety and prestige. Social classes played various roles, in a theatrical sense, engaging in social performance under the freshly consecrated counter-reformation church facades. The new architectural styles that emerged in the cityscape shaped the aura of the city, oppressive and opulent, as the Papacy made itself known in every corner of the town. God became even more tangible and omnipresent to the casual citizen, as every monument served as a visual reminder of Providence's power.

Rome began to modernize, and yet she still had one foot in the past. This liminal, magical, and transitory period of the Eternal city is always in the forefront of my imagination. Baroque Rome is a fantasy world in which I can escape, a unified spectacle, a theater, where lavish displays and Christian piety collapse into one. And in my coral-colored palace of the past, I am granted glimpses of the future. In the words of Peter Rietbergen:

“Indeed, after a first glance at the available material, I felt that such persons were indeed so inclined: most of the sources that fall in the category of texts chronicling the Town’s daily life seem to record the many visible manifestations of power: power temporal, power spiritual and, of course, power supernatural. They concern the rituals of a capital that was excessively attuned to the outward manifestations of the complex power system that, within the theatre that was Rome, centred around the pope, his family and all the other persons and institutions that, together, embodied the Church which was the vessel of those powers.”

Back when theater kids believed in God and managed to entertain.

Today we will be exploring some excerpts from the journal of a first-hand observer of this magical period. A man named Giacinto Gigli (1594-1671). What I find so striking about his journal entries is that there is a complete continuity between the miraculous and the mundane. He records both with the dispassionate eye of a true journalist.

Most of these excerpts will be taken from the fantastic book, Power and Religion in Baroque Rome, by Peter Rietbergen.

__________________

Before getting to the meat of the article, the tales of the miraculous, we first must conceptualize how Rome in this era functioned. In Baroque Rome, the topography and flow of the city became centered around various nodes, the piazze.

“To Gigli, the entire city seems an archipelago, made up of islands of power: power temporal, with sometimes entire wards but, more often, squares and piazze dominated by the palaces of the Roman nobility— there’s a ‘Piazza dei Signori Colonna’, a ‘Piazza dei Signori Farnesi’, and now, of course, a ‘Piazza dei Signori Barberini’, as well—but also power spiritual, as in the case of the big churches and the adjoining monasteries, dominated by the various religious Orders: a ‘Piazza dei Padri Gesuiti’, et cetera. Whenever there is an occasion to celebrate, both noblemen and religious corporations use their part of town, including the surrounding houses and apartment buildings, as a ‘theatre’. Thus, during the ceremonies accompanying the formal declaration of the 26 martyrs who died for their efforts in spreading the faith in Japan and had already worked many miracles, the Jesuits, counting three of their Order among this number, organised a marvelous feast, decking the façades of the Gesù and the adjacent houses with coloured lights and exhibiting a big canvas by the famous painter Arpino showing their three martyrs. The Franciscans, who had contributed the other blood witnesses, had shown theirs in the church of Aracoeli.”

This is such a fantastic image. The whole city itself is a collection of “islands of power,” every square dominated by a different family or religious order, visual testaments to their power, with clearly demarcated spaces under their control. Each with its own unique ceremonies and lines of patronage, each with its own unique flavor, competing with each other to create public beauty while honoring God. This clear demarcation of space, there is something so viscerally appealing about this to me. In our current era, the geography of the city and its social contours have dissolved into a gray mass of confusion. The troglodytes in charge of modern city planning have destroyed any aesthetic or logical sense in the urban environment. Beauty is intentionally subverted, social groupings intentionally torn apart and refigured, as the mad scientists posturing as bureaucrats run social experimentation on natural communities, turning the modern city into a putrid Petri dish.