After Submission

Huysmans and Houellebecq

The first time I sat down to read Houellebecq’s novel Submission, I felt as if I had been robbed.

With a mix of awe and horror, I stared at the selected quotation on the first page.

A noise recalled him to Saint-Sulpice; the choir was leaving; the church was about to close. “I should have tried to pray,” he thought. “It would have been better than sitting here in the empty church, dreaming in my chair—but pray? I have no desire to pray. I am haunted by Catholicism, intoxicated by its atmosphere of incense and candle wax. I hover on its outskirts, moved to tears by its prayers, touched to the very marrow by its psalms and chants. I am revolted with my life, I am sick of myself, but so far from changing my ways! And yet … and yet … however troubled I am in these chapels, as soon as I leave them I become unmoved and dry. In the end,” he told himself, as he rose and followed the last ones out, shepherded by the Swiss guard, “in the end, my heart is hardened and smoked dry by dissipation. I am good for nothing.”

Houellebecq had begun his book with an excerpt from Huysmans “En Route.” But not just any excerpt, it was one that I was all too familiar with. I had highlighted and set it aside a few months prior when I first read Huysmans’ Durtal series. I was adamant that this paragraph, with its flowery description of spiritual desiccation, would serve as the perfect introduction to a novel I was writing.

And he stole it from me. At that moment, I understood Salvador Dali’s rage and frustration when he got up at a young film makers screening and exclaimed “You stole the idea from my subconscious!” I was so deflated, so shocked by this crime, that I would end up abandoning the story I was writing entirely.

But the indignation quickly gave way to a kind of ecstasy. I had known nothing of Houellebecq or this novel that I held in my hands, except that it was scorned by the press as some sweaty French polemic against Muslims, a new Camp of the Saints, and that the author’s name was synonymous with both exquisite prose and Islamophobia. What I was not expecting was Huysmans.

And then I turned the page.

Through all the years of my sad youth Huysmans remained a companion, a faithful friend; never once did I doubt him, never once was I tempted to drop him or take up another subject; then, one afternoon in June 2007, after waiting and putting it off as long as I could, even slightly longer than was allowed, I defended my dissertation, “Joris-Karl Huysmans: Out of the Tunnel,” before the jury of the University of Paris IV–Sorbonne.

The narrator François was a Husymans scholar. And in a flash, my mind began to mull over this revelation, that a novel centered around an Islamic takeover of France was narrated by a Huysmans scholar—and a terrible shiver of awe came over me— the possibility that I may be beginning to read a work of profound genius. A juxtaposition so perfect and with such potential, and even better, one that would be totally incomprehensible to the English-speaking world of literature. What a beautifully French “Fuck You” to the Anglosphere.

And so from the first two pages of this book, I became an admirer of the author. I had been both brutally robbed and astonished by a few lines of ink.

I finished Submission in one sitting. But allowing yourself to consume a book so quickly can be dangerous. You tend to miss details, and you lack time to digest.

My suspicions were confirmed. It was a work of genius, one of the best bits of fiction I had stumbled across in years. The media was wrong of course, which should not come as a shock. This was not an Islamophobic work at all, in fact, it bordered upon Islamophilic. My first sitting with Submission had convinced me of several things. At its core, Submission was a satire of modern academics. “Satire” may be too kind a word, it was more of an indictment. Their insipid lives, their utter lack of personal conviction, how they are nothing more than plastic bags blowing across a deserted beach. Their integrity and commitment analogous to that of the prostitutes that Francois spends half the book joylessly screwing. More than happy to change banners and creeds for a higher salary and a teenage bride. A quote from St Jude comes to mind.

These people are blemishes at your love feasts, eating with you without the slightest qualm—shepherds who feed only themselves. They are clouds without rain, blown along by the wind; autumn trees, without fruit and uprooted—twice dead. They are wild waves of the sea, foaming up their shame; wandering stars, for whom blackest darkness has been reserved forever.

But Submission was also an indictment of modern man’s soul. When I first read the book, I marveled at how Houellebecq contrasted Francois's journey to faith with Huysmans. The spiritually withered and anemic Francois attempts to follow in Huysmans footsteps, to make the romantic leap to faith, to journey in search of himself. But he fails. Halfway through the book he makes the pilgrimage to the Black Madonna of Rocamadour, and he experiences the inklings of a mystic longing, on the very cusp of a theophany, before blaming it on an empty stomach and returning home. In the end, he will not find faith, but he will find religion. He converts to Islam for a high paying job, social prestige, and hand-picked wives. At the time I considered this the perfect juxtaposition, Francois's inability to experience an interior religious ignition due to modernity's shallow capacity for transcendence, vs Huysmans/Durtal’s sincere and permanent conversion to the Catholic Faith. Atleast, this is how I saw it at the time. At this point, I was still too intoxicated with Huysmans to interpret it any differently.

_______________

A few years have passed since that first sitting in the park, from that first experience with Houellebecq, and I decided to revisit his work. This desire was kindled after a conversation with a friend at a bar on the matter of the recent French elections. It has been nine years since the book was published, and the friend in question is convinced that Houellebecq’s observations were damn near prophetic in their accuracy. Upon rereading, I am not so sure. I still believe it is a work of genius but for very different reasons.

Let’s begin with what Houellebecq got wrong.

Houellebecq does not understand Islam. There is great irony in a literary masterpiece failing to capture its central theme. But Submission is not truly a book about the Prophet Mohammed’s faith, and so the point is moot. His admiration for the patriarchal aspects of Islamic culture, his suspicions that it fosters a kind of true sexual possibility and potency that is lost in the West, are orientalist to the core.

Hidden all day in impenetrable black burkas, rich Saudi women transformed themselves by night into birds of paradise with their corsets, their see-through through bras, their G-strings with multicolored lace and rhinestones. They were exactly the opposite of Western women, who spent their days dressed up and looking sexy to maintain their social status, then collapsed in exhaustion once they got home, abandoning all hope of seduction in favor of clothes that were loose and shapeless.

This is pure fantasy. The matriarchal longhouse culture that is engendered by polygamy is worse than anything in the west. He also seems to be under the assumption that Islamic polygamy is still a widespread institution, or that it is something akin to an Ottoman Sultan’s Harem, a “Stately Pleasure Dome Decree.”Houellebecq’s Islam is staunchly patriarchal in its gender relations, in his tale you depict a suspicion that sharia has a real chance of restoring the sexual electricity between man and wife that has been lost in the West. But there is a reason Saudis love their prostitutes, and one thing the author does get right is that after the Islamic takeover, the call girls continue to work unhindered.

But this is peanuts compared to his gravest error, his societal prognosis of French Muslims. The driving political force of Submission is a politician known as Mohammed Ben Abbes. A refined and charismatic political operator who united the Islamic factions and consolidated power over France. From there he spreads his influence and revives Frances's imperial empire and more. A humble son of a Tunisian grocer. The Catholics and secularists even grow to adore him.

Nine years after the publishing of Submission and France has no Mohammed Ben Abbes. No great man has arisen as Ben Abbes did from the French Islamic neighborhoods. There are no French Muslims with sophisticated economic plans for a new Islamic empire. There is only a reactionary, third-world resentment. There is no vision, only the scorn of the lumpenproletariat.

In this sense, Houellebecq reveals himself to be so stunningly French. Even in his pessimistic predictions, he believes that a French Tunisian son of a grocer could become an Arab Napoleon. And it should be a source of great hope for French Nationalists that Houellebecq was wrong, that Republican France was wrong in her racial optimism.

But as the recent elections attest, Houellebecq had a prophetic accuracy in regard to the rest of French politics.

“Trust me, no one can prove anything, one way or the other—and no one’s going to try. Politically, though, big things are going to happen. And fast. We’ll see as soon as tomorrow. One possibility is that the UMP will decide to form a coalition with the National Front. So what, you say—the UMP are in free fall. Still, they’re enough to tip the balance and win the election.” “I don’t know. If they were going to ally themselves with the National Front, couldn’t they have done it years ago?” “Exactly right!” he beamed. “At the beginning, the National Front was eager to team up with the UMP so they could form a governing majority. Then, gradually, the National Front grew. Their numbers went up in the polls, and the UMP started to get scared. Not of their populism, or their supposed fascism—the leaders of the UMP wouldn’t have minded a few new security measures, a little xenophobia. UMP voters, such as they are, are all for that sort of thing. But as a practical matter, the UMP is very much the weaker partner in this alliance. If they make a deal, they’re afraid of being annihilated and simply absorbed into the National Front. And finally there’s Europe. That’s the deal killer. What the UMP wants, and the Socialists, too, is for France to disappear—to be integrated into a European federation. Obviously, this isn’t popular with the voters, but for years the party leaders have managed to sweep it under the rug. If they formed an alliance with an openly anti-European party, they couldn’t go on this way, the whole thing would fall apart. That’s why I lean toward a second scenario, the creation of a republican alliance, where the UMP and the Socialists both get behind Ben Abbes—as long as they can get enough seats to form a government.”

His only mistake was thinking the Muslims could organize behind one of their own, a great man, a political messiah. His calculus was off. And thank God for it.

The Islam in Submission is an invention of the author, a literary foil for all he sees wrong with France. What he does understand is Huysmans. And he understands modern Catholicism, he perceives it so clearly and lucidly, without overtly saying much about it at all. And it’s a damning judgment.

Submission contains one of the most brutal and violent assaults on Joris Karl Huysmans legacy and personage ever put to paper. A literary disembowelment of his conversion to Catholicism and the impulse that brought his generational milieu to the Church in the first place. I’m not sure how I missed this violence the first time. Maybe I was just too Catholic, too freshly enamored with Huysmans.

As stated in the beginning, I had discovered Huysmans a few months before reading Submission. I began with A Rebours. But it wasn’t A Rebours that gripped me. It was the Durtal trilogy. I was spellbound— bewitched— brought to God by those books. His intoxicating elixir of spiritualism and aesthetic ecstasies, it transfigured me. Huysmans ability to use language to describe works of art, almost repainting the works in his descriptions, adding new hues with ink, transmuting the brush strokes of the masters into something even more lofty. I felt greater awe and beauty reading him describe a painting than I did looking at the painting itself. It was not glimpsing Grunewalds Crucifixion that made me a catholic, but reading Huysmans description of it:

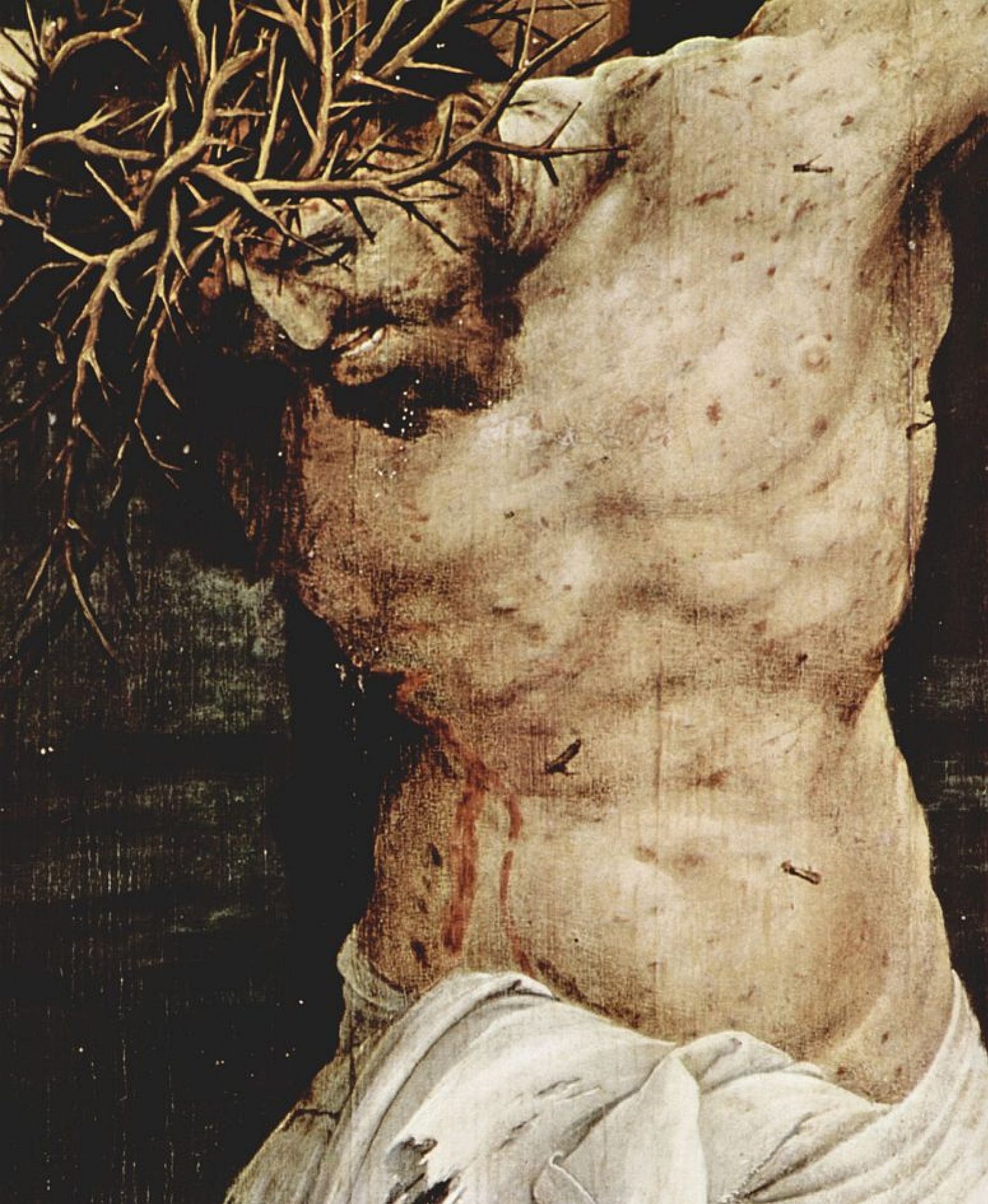

Durtal's introduction to this naturalism had come as a revelation the year before, although he had not then been so weary as now of fin de siècle silliness. In Germany, before a Crucifixion by Matthæus Grünewald, he had found what he was seeking.

He shuddered in his armchair and closed his eyes as if in pain. With extraordinary lucidity he revisualized the picture, and the cry of admiration wrung from him when he had entered the little room of the Cassel museum was reechoing in his mind as here, in his study, the Christ rose before him, formidable, on a rude cross of barky wood, the arm an untrimmed branch bending like a bow under the weight of the body.

This branch seemed about to spring back and mercifully hurl afar from our cruel, sinful world the suffering flesh held to earth by the enormous spike piercing the feet. Dislocated, almost ripped out of their sockets, the arms of the Christ seemed trammelled by the knotty cords of the straining muscles. The laboured tendons of the armpits seemed ready to snap. The fingers, wide apart, were contorted in an arrested gesture in which were supplication and reproach but also benediction. The trembling thighs were greasy with sweat. The ribs were like staves, or like the bars of a cage, the flesh swollen, blue, mottled with flea-bites, specked as with pin-pricks by spines broken off from the rods of the scourging and now festering beneath the skin where they had penetrated.

Purulence was at hand. The fluvial wound in the side dripped thickly, inundating the thigh with blood that was like congealing mulberry juice. Milky pus, which yet was somewhat reddish, something like the colour of grey Moselle, oozed from the chest and ran down over the abdomen and the loin cloth. The knees had been forced together and the rotulæ touched, but the lower legs were held wide apart, though the feet were placed one on top of the other. These, beginning to putrefy, were turning green beneath a river of blood. Spongy and blistered, they were horrible, the flesh tumefied, swollen over the head of the spike, and the gripping toes, with the horny blue nails, contradicted the imploring gesture of the hands, turning that benediction into a curse; and as the hands pointed heavenward, so the feet seemed to cling to earth, to that ochre ground, ferruginous like the purple soil of Thuringia.

Above this eruptive cadaver, the head, tumultuous, enormous, encircled by a disordered crown of thorns, hung down lifeless. One lacklustre eye half opened as a shudder of terror or of sorrow traversed the expiring figure. The face was furrowed, the brow seamed, the cheeks blanched; all the drooping features wept, while the mouth, unnerved, its under jaw racked by tetanic contractions, laughed atrociously.

The torture had been terrific, and the agony had frightened the mocking executioners into flight.

Against a dark blue night-sky the cross seemed to bow down, almost to touch the ground with its tip, while two figures, one on each side, kept watch over the Christ. One was the Virgin, wearing a hood the colour of mucous blood over a robe of wan blue. Her face was pale and swollen with weeping, and she stood rigid, as one who buries his fingernails deep into his palms and sobs. The other figure was that of Saint John, like a gipsy or sunburnt Swabian peasant, very tall, his beard matted and tangled, his robe of a scarlet stuff cut in wide strips like slabs of bark. His mantle was a chamois yellow; the lining, caught up at the sleeves, showed a feverish yellow as of unripe lemons. Spent with weeping, but possessed of more endurance than Mary, who was yet erect but broken and exhausted, he had joined his hands and in an access of outraged loyalty had drawn himself up before the corpse, which he contemplated with his red and smoky eyes while he choked back the cry which threatened to rend his quivering throat.

Ah, this coarse, tear-compelling Calvary was at the opposite pole from those debonair Golgothas adopted by the Church ever since the Renaissance. This lockjaw Christ was not the Christ of the rich, the Adonis of Galilee, the exquisite dandy, the handsome youth with the curly brown tresses, divided beard, and insipid doll-like features, whom the faithful have adored for four centuries. This was the Christ of Justin, Basil, Cyril, Tertullian, the Christ of the apostolic church, the vulgar Christ, ugly with the assumption of the whole burden of our sins and clothed, through humility, in the most abject of forms.

It was the Christ of the poor, the Christ incarnate in the image of the most miserable of us He came to save; the Christ of the afflicted, of the beggar, of all those on whose indigence and helplessness the greed of their brother battens; the human Christ, frail of flesh, abandoned by the Father until such time as no further torture was possible; the Christ with no recourse but His Mother, to Whom—then powerless to aid Him—He had, like every man in torment, cried out with an infant's cry.

In an unsparing humility, doubtless, He had willed to suffer the Passion with all the suffering permitted to the human senses, and, obeying an incomprehensible ordination, He, in the time of the scourging and of the blows and of the insults spat in His face, had put off divinity, nor had He resumed it when, after these preliminary mockeries, He entered upon the unspeakable torment of the unceasing agony. Thus, dying like a thief, like a dog, basely, vilely, physically, He had sunk himself to the deepest depth of fallen humanity and had not spared Himself the last ignominy of putrefaction.

Never before had naturalism transfigured itself by such a conception and execution. Never before had a painter so charnally envisaged divinity nor so brutally dipped his brush into the wounds and running sores and bleeding nail holes of the Saviour. Grünewald had passed all measure. He was the most uncompromising of realists, but his morgue Redeemer, his sewer Deity, let the observer know that realism could be truly transcendent. A divine light played about that ulcerated head, a superhuman expression illuminated the fermenting skin of the epileptic features. This crucified corpse was a very God, and, without aureole, without nimbus, with none of the stock accoutrements except the blood-sprinkled crown of thorns, Jesus appeared in His celestial super-essence, between the stunned, grief-torn Virgin and a Saint John whose calcined eyes were beyond the shedding of tears.

These faces, by nature vulgar, were resplendent, transfigured with the expression of the sublime grief of those souls whose plaint is not heard. Thief, pauper, and peasant had vanished and given place to supraterrestial creatures in the presence of their God.

Grünewald was the most uncompromising of idealists. Never had artist known such magnificent exaltation, none had ever so resolutely bounded from the summit of spiritual altitude to the rapt orb of heaven. He had gone to the two extremes. From the rankest weeds of the pit he had extracted the finest essence of charity, the mordant liquor of tears. In this canvas was revealed the masterpiece of an art obeying the unopposable urge to render the tangible and the invisible, to make manifest the crying impurity of the flesh and to make sublime the infinite distress of the soul.

It was without its equivalent in literature. A few pages of Anne Emmerich upon the Passion, though comparatively attenuated, approached this ideal of supernatural realism and of veridic and exsurrected life. Perhaps, too, certain effusions of Ruysbroeck, seeming to spurt forth in twin jets of black and white flame, were worthy of comparison with the divine befoulment of Grünewald. Hardly, either. Grünewald's masterpiece remained unique. It was at the same time infinite and of earth earthy.

"But," said Durtal to himself, rousing out of his revery, "if I am consistent I shall have to come around to the Catholicism of the Middle Ages, to mystic naturalism. Ah, no! I will not—and yet, perhaps I may!"

These words to me were more precious, more honey-sweet and sublime, than the entirety of the Gospels. “Sacrilege!” You may cry, but reading those words— dear reader— reading those lines made Jesus of Nazareth something more than a man to me. In a way that Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John had all failed.

Huysmans was my evangelist, he was my reason for returning to the Catholicism that I had abandoned as a teenager. My conversion was Husymans conversion, for the same reasons, out of the same impulse, the same leap from admiring the church’s aesthetic treasures, to finding her dogma beautiful too. He held my hand all the way.

Only now can I see the violence in Houellebecq’s story, the violence to Huysmans, the violence to his conversion, the violence to my conversion.

And now I think the bastard is right.

I could now write out a long essay, an essay comparing Huysmans and his proxy Durtal’s conversion and journey with Houellebecq’s Francois. A really great analysis that would make some English professors gush red and maybe get me some pats on the back for the insight. But I am not going to do that.

All of the anglosphere journalists and reviewers did not understand Submission because they did not understand Huysmans. And the handful of them that did only compared Submission to Huysmans’ A Rebour, because it was the only book of his that they read.

Houellebecq was not contrasting Durtals conversion with his own character Francois’. He was not making the point that 100 years ago a man could still have an inner religious consecration of the heart, while today man is so degenerate and fragile that he only converts for material gain. No. Houellebecq was showing that Huysmans’ conversion was no more virtuous or ignoble than Francois’. The high-minded discussions of religion and art that occur in the Durtal series are no more vapid and hollow than Francois incessant chatter of politics and his mindless sex.

And yet, in an unpleasant way, I couldn’t help seeing that these human beings were just like me, and it was this very resemblance that made me avoid them. I should have found a woman to marry. That was the classic, time-honored solution. A woman is human, obviously, but she represents a slightly different kind of humanity. She gives life a certain perfume of exoticism. Huysmans would have posed the problem in almost exactly the same terms. Not much had changed since then, except in an incidental and negative way, through slow erosion and leveling—but no doubt even this leveling, these changes, had been greatly exaggerated. In the end Huysmans had taken another path, he had chosen the more radical exoticism of religion; but that path still left me just as perplexed as the other.

In these lines, I finally saw it.

Houellebecq is claiming that Huysmans conversion, his pilgrimage through aesthetic wonder to religious certainty, was nothing more than another method of self-abandonment into the appeal of “radical exoticism.” No different than the deracinated Anglo saxon ginger who recites shahada to cloak himself in a new cultural veil. Or the baptist who dips his head into the waters of Eastern Orthodoxy for the mystique of incense and foreign chants. Is this route, Husymans route, my route, from aestheticism to religious Orthodoxy, not a pure movement, not a truly honest and transcendent shift? Is it but a hollow orientalism? Would the art house hipsters in Brooklyn who fancy themselves trad caths, just as easily join the Ummah if cultured Sufis set up shop next door?

Did À rebours really lead, inevitably, to a return to the Church? In the end Huysmans did return to the Church, and clearly he meant it. Les foules de Lourdes, his last book, was authentically the work of a Christian, in which the misanthropic aesthete and loner overcomes his aversion to religious trinkets and finally allows himself to be carried away by the simple faith of the pilgrims at Lourdes. On the other hand, practically speaking, this return didn’t require much in the way of personal sacrifice: as a lay brother at Ligugé, Huysmans was allowed to live outside the monastery. He had his own housekeeper, who cooked him the bourgeois meals that played such a prominent role in his life. He had his library and his packets of Dutch tobacco. He did all the offices, and no doubt he enjoyed them: his aesthetic, almost carnal delight in the Catholic liturgy comes through on every page of his later books. As for the metaphysical questions that Rediger had raised the night before, Huysmans never mentions them. The infinite spaces that terrified Pascal, that inspired in Newton and Kant such awe and respect, Huysmans seems never to have noticed. He was a convert, certainly, but not along the lines of Péguy or Claudel. My own dissertation, I now realized, would not be much help to me; and neither would Huysmans’s own protestations of faith.

Maybe the old allegory of the Church being a woman is more pessimistic than I had ever imagined. Maybe Huysmans oblate vows were worth nothing more than Francois assigned harem.

Francois attempts to follow his hero Huysmans footsteps into faith. He even comes close to a mystical experience in front of a statue of a Black Madonna. But he abandons it, and when he comes home, he finds that his own mother died alone while he was away.

Francois ends up converting to Islam at the end of the book, to keep his job at the new Islamic university, and is given buxom wives to keep him warm. A fat paycheck and scholarly recognition. He even convinces himself of the Islamic arguments for God. The arguments for submission. When I first read this I found it witty and biting satire. Now I am filled with tragedy, for it was in a way no different from Huysmans. In the end, Francois conversion was internal too. But without suffering. Without the precious Christian suffering that I was led to believe was so crucial for religion.

Houellebecq saw with complete lucidity the weakness of French Catholicsm, with modern Catholicism. When the character who converts Francois admits that he was a Catholic in the nativist movements in his youth. And the reason for his converter’s conversion?

The question was, could Christianity be revived? I thought so. I thought so for several years—with growing doubts. As time went on, I subscribed more and more to Toynbee’s idea that civilizations die not by murder but by suicide. And then one day everything changed for me. It was March thirtieth, 2013, I’ll never forget—Easter weekend. At the time I was living in Brussels, and every once in a while I’d go have a drink at the bar of the Métropole. I’d always loved Art Nouveau. There are magnificent examples in Prague and Vienna, and there are interesting buildings in Paris and London, too, but for me—right or wrong—the high point of Art Nouveau decor was the Hotel Métropole de Bruxelles, in particular the bar. The morning of March thirtieth, I happened to walk by and saw a sign that said the bar of the Métropole was closing for good, that very night. I was stunned. I went in and spoke to the waiters. They confirmed it; they didn’t know the exact reasons… I spent that last night at the Métropole, until it closed. I walked all the way home, halfway across the city, past the EU compound, that gloomy fortress in the slums. The next day I went to see an imam in Zaventem. And the day after that—Easter Monday—in front of a handful of witnesses, I spoke the ritual words and converted to Islam.”

________

Huysmans was an aesthete, and Francois was not. Maybe it was this reason that the sacred magnetism of the Church could not bewitch his soul. But if it is simply Renaissance frescos and Gregorian chants that can manage to bind a man to the Catholic God, then another radical exoticism will win out, an exoticism that brings with it a political system, a fat paycheck, and young wives, as is the case with Houellebecq’s Islam. For the great catholic painters are all in the ground, their knuckles and tendons withered with the worms. And the monastic chants that Huysmans enjoyed in Paris are leaving the air, the harmony and treasures no longer producible, and the old ones are slowly smoldering into smoke.

If aesthetics bring a man to God, then any God will do. Especially if the new God brings with him a paycheck and a bride too.

I find myself feeling cold. The ancient basilicas no longer enchant me. The brush strokes of Raphael leave me sick. Houellebecq may have overestimated Islam, but he diagnosed a deeper sickness.

And I think back to the last words of La Bas.

"Oh, God!" murmured Durtal forlornly, "what whirlwinds of ordure I see on the horizon!"

"No," said Carhaix, "don't say that. On earth all is dead and decomposed. But in heaven! Ah, I admit that the Paraclete is keeping us waiting. But the texts announcing his coming are inspired. The future is certain. There will be light," and with bowed head he prayed fervently.

Des Hermies rose and paced the room. "All that is very well," he groaned, "but this century laughs the glorified Christ to scorn. It contaminates the supernatural and vomits on the Beyond. Well, how can we hope that in the future the offspring of the fetid tradesmen of today will be decent? Brought up as they are, what will they do in Life?"

"They will do," replied Durtal, "as their fathers and mothers do now. They will stuff their guts and crowd out their souls through their alimentary canals."