I Am Not What I Am: JAGO Revisited

The Moor and his Bride

Almost two years have passed since I first published my article on the artist Jago and the bizarre matrix of symbols that haunt his oeuvre like ghosts. And as anyone who has seen Jago’s work can attest— these ghosts are a bit lacking in taste. Jago’s talent as an artist is so paltry, his statues so kitsch, that the aesthetic value of his work is even more offensive than it is sacrilegious. The concerted effort by the media and the church to paint the sculptor as a new Michelangelo is a sin against art and an insult to anyone with eyes. In Mozambique, there is a folk belief that bald men have gold in their heads, but one look at Jago’s Pieta proves that his skull is full of nothing but pyrite— fools gold with hints of sulfur.

Jago and his creations had not crossed my mind in many months, (surely a great mercy from God), that is up until a few weeks ago when I noticed a poster outside the theater near my apartment. It appears that the powers that be have gifted him his own documentary.

I decided that this was as good a time (sign?) as any to revisit our favorite astroturfed sculptor.

_______________

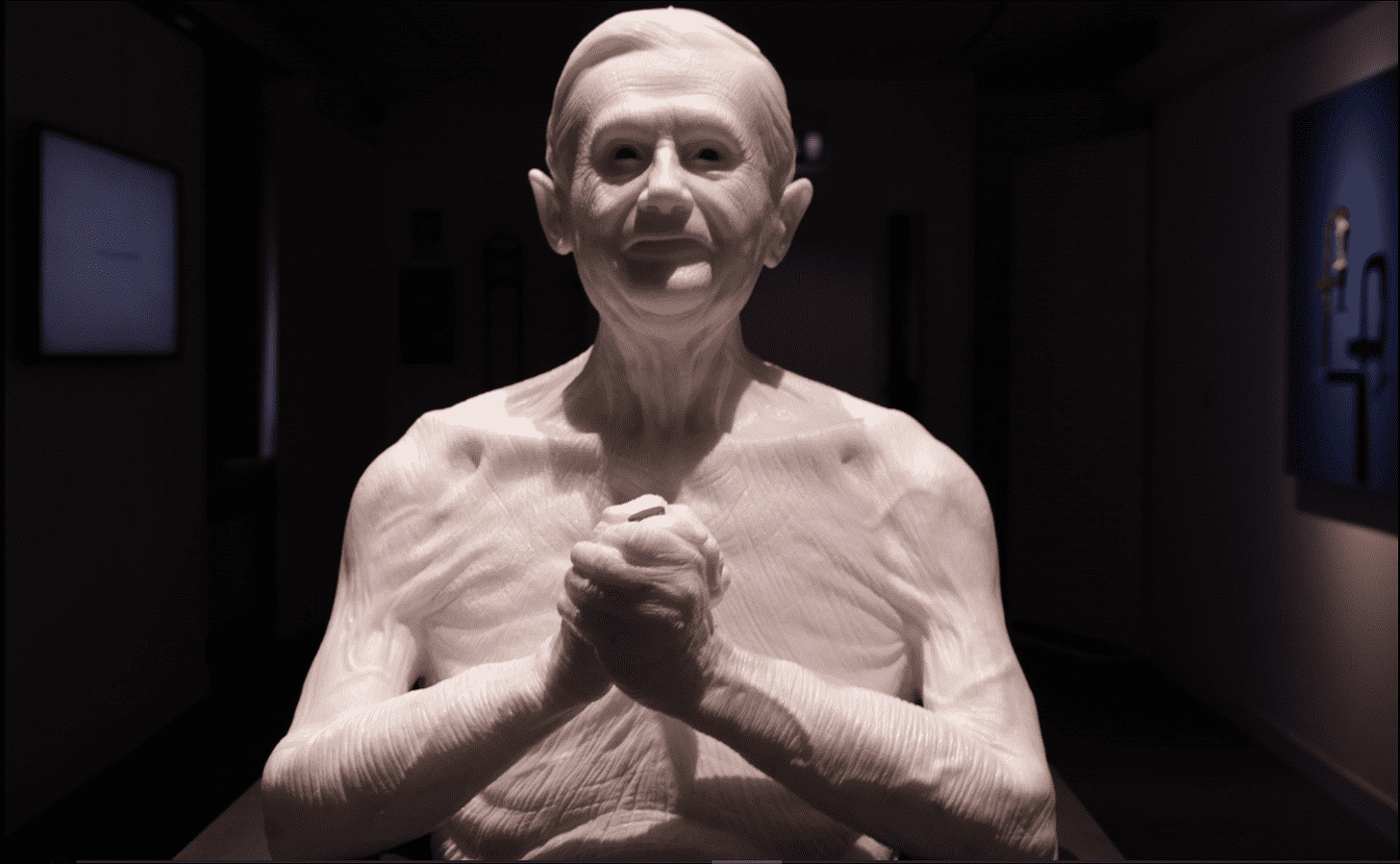

Jacopo Cardillo’s (born 1987) meteoric rise from a nobody to a darling of the art world occurred practically overnight. (There is a thief pun to be made somewhere). The earliest listed work of his is Ego laurentius which was produced in 2007. The narrative usually makes it out as if in 2009 he exploded in popularity with his bust of Pope Benedict XVI. This bust attracts the attention of the Vatican and the art world, and it begins his long relationship with the Church as his patron. Then, as the story goes, in 2013 Jago had the “genius” idea to alter the bust after Benedict XVI resigned. He strips the statue of its vestments, the symbols of papal authority, leaving wrinkled and veristic flesh underneath. Two elements are noteworthy. He adds the missing eyes to the bust, and he does not remove the Fisherman’s Ring. The altered work was titled Habemus Hominem. From this point, his career takes off, both with the Church and the art world at large.

But there are many issues with this narrative.

The original bust was very uncharacteristic of Jago. The statue was completely lacking in the signature detail that characterizes Jagos work. The statue also lacked eyes. In 2009 the statue looked, well, unfinished. After Benedict’s resignation, he chips away the smooth vestments to reveal the intricate body beneath. And he adds eyes to the statue. Uncanny eyes that follow you. (Again, reread the original article). It was a very specific optical effect, one which it’s hard to believe could have been added if he did not already have it in mind in 2009.

But how could some art world nobody in 2009 predict that Benedict would one day resign?

A year and a half ago, I speculated that the statue may have been commissioned by a shadowy patron with foreknowledge of this resignation, with the intention of stripping the bust away when Ratzinger finally stepped down. Sound crazy? Well…

Someone in the Vatican actually commissioned him to create the original bust. (source 1) (source 2). Why— and who— in the Church chose Jago, a nobody at the time, for this work?

In 2012, Jago received a Pontifical Medal for his unfinished bust of Benedict, from Cardinal Ravasi and Cardinal Bertone. (Source.) If you do not recognize the name Bertone, I will quote the last article:

Cardinal Bertone. A wicked, terrifying figure. Believed to be one of the kingmakers behind the ascension of Pope Francis, and all the machinations involved. At the time the Secretary of State for the Holy See. There are also reports that he was part of the alteration and cover up of the Third Secret of Fatima, that he was behind the dismissal of Abp Vigano. Remember, it was Vigano who was investigating the IOR (Vatican Bank) and the massive corruption and money laundering that was occurring there. Bertone is accused of “mismanaging” millions of IOR money, and lived and extremely lavish lifestyle. He is also widely believed to be a Freemason.

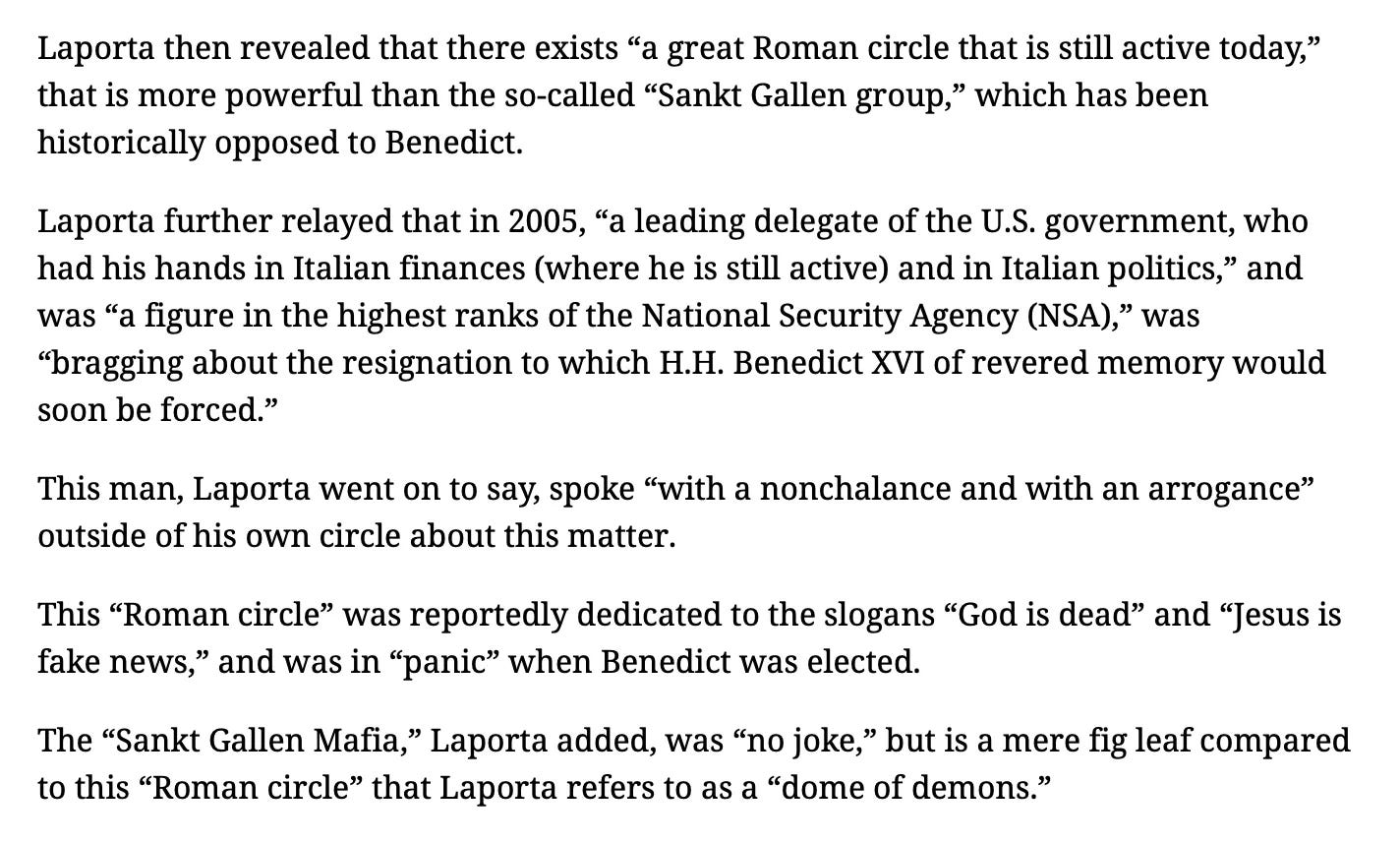

In the last article, we advanced the thesis that Jago’s benefactors picked the young man to play a specific artistic role. To advance certain themes and symbols. I hypothesized that whoever these individuals were, they played a part in the intimidation and coercion of Pope Benedict XVI, and that they had ties to clerical masonry. Anyone who has been following my work knows this is not far-fetched. As the reputable Italian Brigadier General Laporta stated:

But I do not want to spend this article covering old ground. It is my intention to bring forward new information, advancing and confirming my thesis.

Let us begin with the Masonic angle. I would like to touch on a new discovery of mine that reinforces the fact that Jago is explicitly employing masonic imagery in his work.

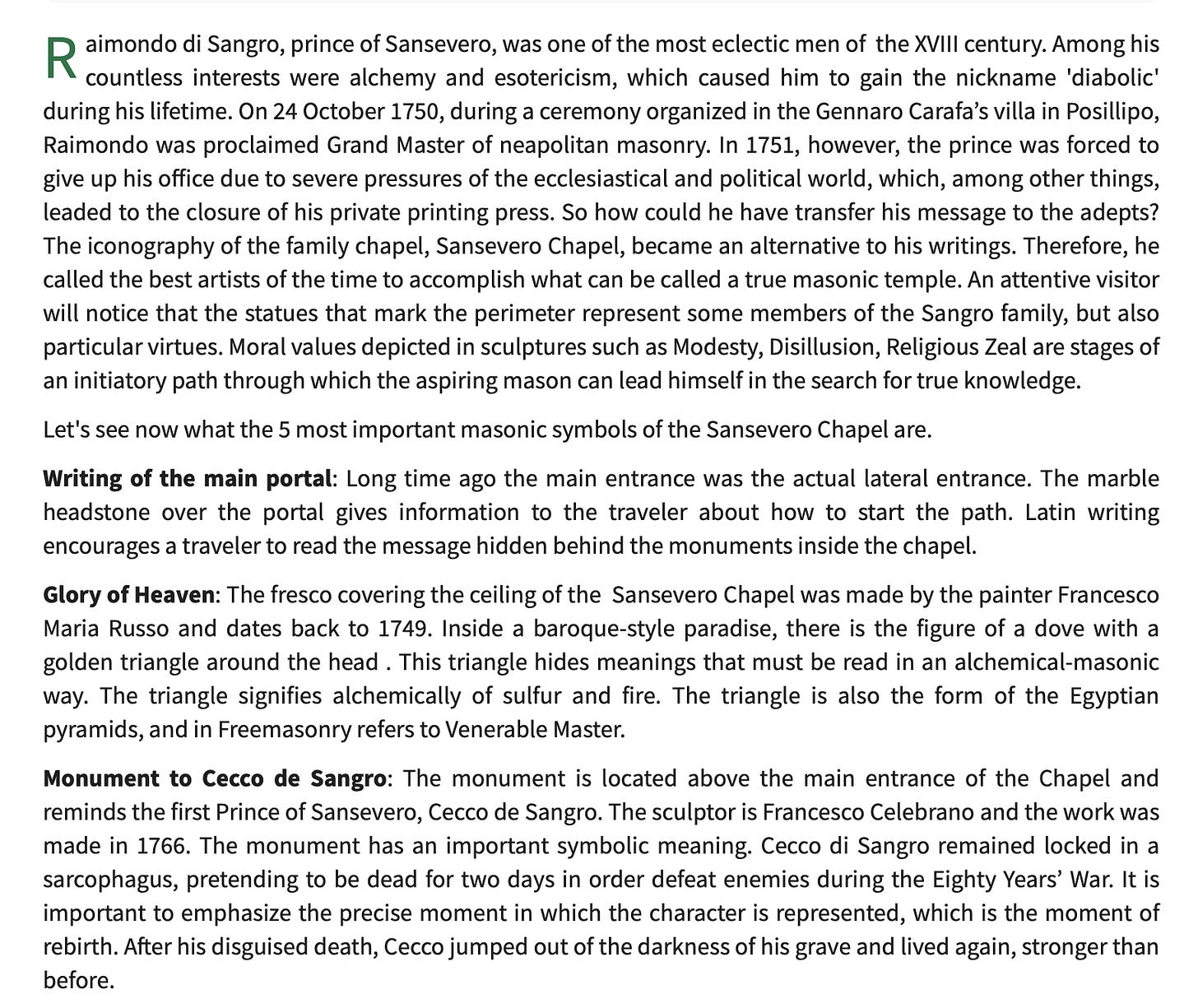

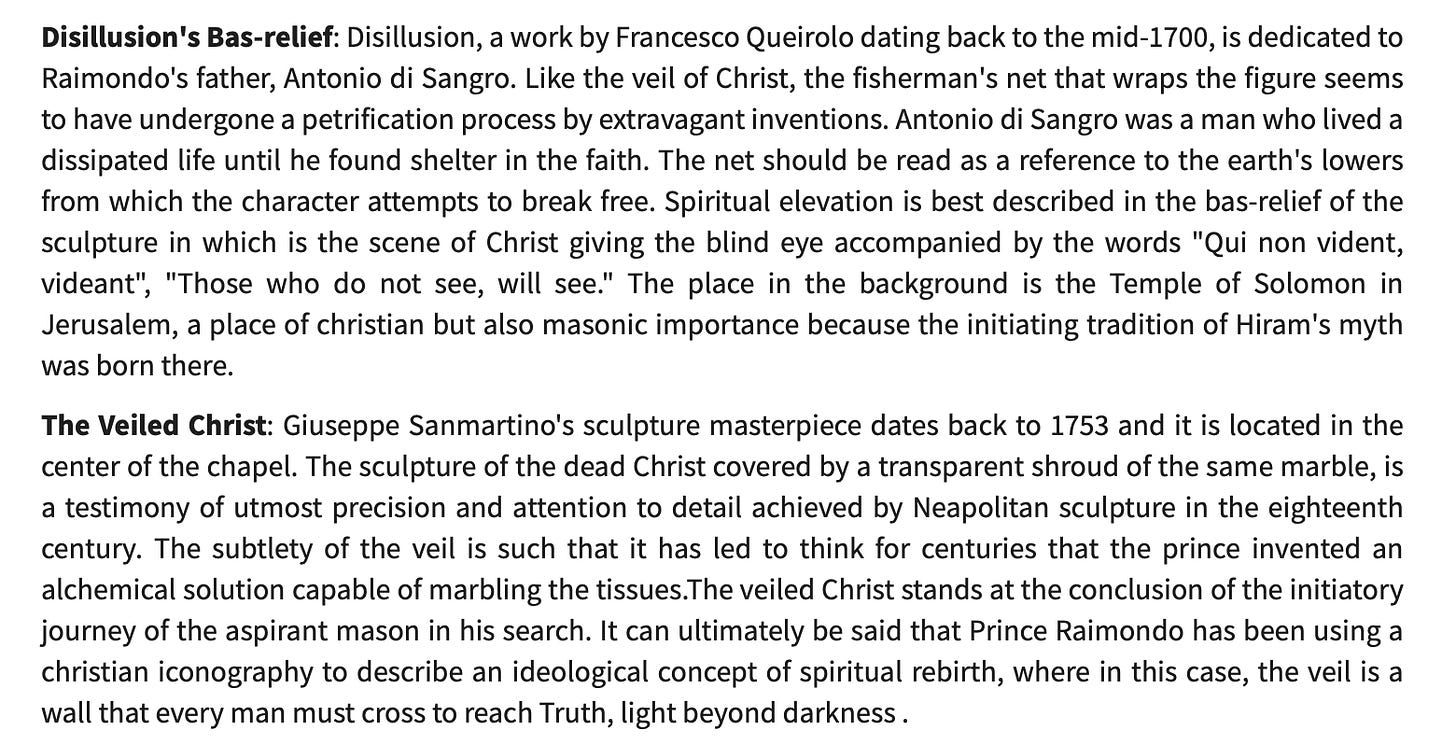

As discussed previously, Jago’s Veiled Son (2019) was explicitly based on the Veiled Christ of the Sansevero Chapel, and to further the connection to the original work, Jago’s statue was also for a time exhibited in the same building.

And what is even more fascinating, and damning, is the story behind the original Veiled Christ statue and the church it is in. The Sansevero Chapel. A Chapel explicitly linked to Freemasonry. Probably the most explicitly linked chapel to Freemasonry in the entire world. And this is not some veiled (pardon the pun) conspiracy, this is freely admitted and explained on even the official Naples visitor website. To demonstrate how well known this is, I’ll post an excerpt from the official site on the chapel.

So we have our first masonic commission. I have recently discovered that he had an earlier and lesser-known work, that was even more explicitly masonic. The Monumento al Libero Pensiero (Monument to Free Thought) in Arezzo. It was erected in 2016 and then destroyed, which is why I originally missed it.

The monument was dedicated to Tommaso Baldassarre Crudeli (1702-1745). Crudeli is considered the first martyr of Universal Masonry. Tommaso was initiated in 1735, into an offshoot of the Grand Lodge of England, the first Masonic Lodge in Italy. He was imprisoned and tortured by the Roman Inquisition for his involvement in masonry, eventually succumbing to wounds caused by his captors. For this, he became a masonic martyr. His name is emblematic of the struggle between masonry and the Catholic Church.

So why is an artist whose career was made by the Church, whose work is featured in prominent churches, creating monuments to Freemasonic martyrs who struggled against the Church?

But it gets worse. Jago’s Monumento al Libero Pensiero immediately brings to mind another Monumento al Libero Pensiero, in fact, if you google Jago’s rendition, one of the first search results is the other, the Monumento a Giordano Bruno. The famous statue in Campo de Fiori. A monument that Jago used as inspiration for his own.

This statue was erected in the late 19th century to honor Giordano Bruno. Bruno was not a mason, but he is claimed by Masons as a hero, and Bruno was burned by the church as a heretic. Bruno was a genius, a man I personally admire, and a man who would have despised many aspects of the modern Masonic project. But the erection of this statue was explicitly Masonic.

The statue was unveiled on 9 June 1889, at the site where Bruno was burnt at the stake for heresy on 17 February 1600, and the radical politician Giovanni Bovio gave a speech surrounded by about 100 Masonic flags. Since thousands of individuals and students aligned with anticlerical movements had congregated in Rome for the unveiling, the Vatican had closed the museum and warned local churches and parishes to shutter their doors to avoid confrontations or incidents from what they considered an atheistic mob. In October 1890, Pope Leo XIII issued a further warning to Italy in his encyclical Ab Apostolici against Freemasonry; he commented on the monument in the following passage:

“that eminently sectarian work, the erection of the monument to the renowned apostate of Nola, which, with the aid and favour of the government, was promoted, determined, and carried out by means of Freemasonry, whose most authorised spokesmen were not ashamed to acknowledge its purpose and to declare its meaning. Its purpose was to insult the Papacy; its meaning that, instead of the Catholic Faith, must now be substituted the most absolute freedom of examination, of criticism, of thought, and of conscience: and what is meant by such language in the mouth of the sects is well known.”

And the artist of the Bruno statue is even more revealing. Ettore Ferrari. Ettore was a sculptor and the Grand Master of the Grande Oriente d'Italia, the main Masonic body in Italy. (When he created the statue he was not yet grand master).

Is this what Jago is being groomed to be? This generation of Italian Masons own Ettore Ferrari? Was his Monumento al Libero Pensiero a wink and a nod to Ettore’s?

Jago’s flirtation with Massoneria is undeniable. And the fact that the Papal bust that brought him fame was both commissioned by individuals in the vatican, and seems to imply foreknowledge of Benedicts resignation is too blatant to ignore. But it is time to get far stranger.

__________________

There is much talk lately of “theater kid occupied government” and not enough talk of a “theater kid occupied church.” Much of the Roman clergy seems possessed by the thespian impulse— a flamboyant blend of theatricality and repressed homosexuality— hell, what theater kid does not dream of singing in a choir and playing dress up? A far cry from the days when the church banned secular plays and viewed actors as a louder flavor of prostitute. Theater kids are no strangers to the Throne of Peter. The diary entries of the young Paul VI scream theater kid, as Montini considered Oscar Wilde a personal hero during the days in which the writer was still seen as more degenerate than respectable. And of course, Pope John Paul II was originally a professional actor and the cofounder of an innovative form of theater.

The term “mass ritual” is a bit too heavy-handed. A better term would be “psychodramas” or “public performances” at the societal level. And who better to stage a mass ritu—erm sorry—public performance, than a group of theater kids? Theater kids with a big budget and a faithful audience of 20% of the world? One thing to understand about the scripts of these societal performances is that they are very modernist and referential in the sense that they are drawing on and alluding to everything from history to myth to literature. And what is every theater kids favorite writer? Shakespeare. And ol’ William has the added bonus of having a work inundated with symbolism of the masonic variety. The 20th-century poet Ted Hughes had this to say about Shakespeare. “Everything was ordered to numerical and alphabetical ciphers, secret keys, symbols and sigils that constitute a mnemonic or psychic map of consciousness.” A synopsis of this would require an entire article of its own. Anyone who has read James Shelby Downard or his disciple Michael Hoffman knows that many of the theoretical scripts of mass rituals seem to have nods to the great Bard.

At this point, you are probably wondering where in the world I am going with all of this. Lately, I had a bit of a revelation, a missing piece so obvious that I am not sure how I missed it. The sculptor’s chosen name. JAGO.

When people tell you who they are, you should probably believe them.

Jago, or Iago (there was no letter J until the 16th century, and Jago is a variation of Iago) is indeed the Spanish version of the Italian sculptor’s name, Jacopo. But any mention of Jago/Iago is bound to bring one’s mind to the most famous Iago of them all, the antagonist of Shakespeares’ play Othello.

Anyone familiar with the plot, may begin to feel a shiver down their spine.

The story primarily focuses on two characters, Othello and Iago.

Othello is a Moorish military commander who was serving as a general of the Venetian army in defence of Cyprus against invasion by Ottoman Turks. He had recently married Desdemona, a beautiful and wealthy Venetian lady younger than himself, without the knowledge of and despite the later objection of her father. Iago is Othello's malevolent ensign, who maliciously stokes his master's jealousy until the usually stoic Othello kills his beloved wife in a fit of blind rage.

Iago is a malevolent figure, an expert manipulator whose intentions are veiled. He is a subordinate of Othello, and throughout the play pretends to be Othello’s close friend, all the while manipulating him and plotting against him. Duplicitious and evil. One of his most famous proclamations is as follows:

“Were I the Moor I would not be Iago.

In following him I follow but myself;

Heaven is my judge, not I for love and duty,

But seeming so for my peculiar end.

For when my outward action doth demonstrate

The native act and figure of my heart

In compliment extern, ’tis not long after

But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve

For daws to peck at. I am not what I am.”

I am not what I am. A double meaning is on display here. He is both stating that he is not what he appears to be, that he cannot be trusted, but he is also alluding to something far darker.

Yahweh, the name of God in Hebrew, literally means I am I am. It is widely recognized that Shakespear was inverting the name of God, I AM NOT WHAT I AM.

An utter negation of God, a proclamation of pure darkness. Iago is the closest thing we have in the Shakespearian canon to a living personification of the Father of Lies, the Devil. Quite a name for an artist, no?

But let us take a deeper look at the plot and its themes.

I had certain suspicions in mind when rereading Othello this week during my research. Suspicions that were all but confirmed. The language and imagery of Othello and Desdemona struck me as a strange inversion of the Song of Solomon. What first alerted me was the imagery of black Othello the moor contrasted with white Desdemona, it drew to mind the contrast of Solomon with his black bride in the Biblical Song of Solomon. The Hebrew Song of Solomon or Song of Songs would be reinterpreted by later Christians as an allegory for Christ and his Bride, the Church. I found another author who agreed with my interpretation, that Shakespeares story was far more biblical than normally acknowledged.

This appears strikingly in the second scene of the first act when Shakespeare invents a scene that is not in Cinthio and includes a clear allusion to the Biblical story of the arrest of Christ in the Garden of Gesthemene. The specific language which alludes to the Biblical story is Othello’s command: “Keep up your bright swords” (1.2.59).[10] Naseeb Shaheen offers the following illuminating comments.

“The setting closely parallels the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ arrest. A band with torches and armed with swords comes by night to arrest Othello. The stage direction in the Quarto (1622) says: “Enters Brabantio, Roderigo, and others with lights and weapons.” The stage direction in the Folio is: “Enter Brabantio, Roderigo, with Officers and Torches.” The circumstances of Jesus arrest are much the same. Matthew 26.47; John 18.3.”[11]

As allusions go, this is clear enough in itself, but the fact that Shakespeare here added an incident that is not only not found in Cinthio’s original story but even contradicts Cinthio’s story line[12] indicates clearly that this incident and its Biblical associations are important for what Shakespeare is doing in this play. All the more so, in that it is this scene in which we are finally introduced to the man that Iago had previously described at length in the most unflattering terms (1.1.9ff.). Othello’s calm bearing and courage in the face of extreme danger, like Christ’s in the Bible, draws attention to his dignity and offers dramatic refutation of Iago’s slanders. That impression is only augmented by the trial scene that naturally follows the arrest. Though Othello is more loquacious at his trial than Christ was, his display of dignity, calm rationality, and courage is analogous.[13]

In fact, since the arrest scene is associated with Othello’s marriage to Desdemona, it suggests that Othello is a Christ-like husband to his bride — alluding to the well-known Biblical picture of Christ and His church. Though it may seem too much to regard the marriage of Othello and Desdemona as a picture of the marriage of Christ and the Church, in Elizabethan times the Anglican marriage rite included specific reference to the fact that all marriages signify “unto us the mystical union that is betwixt Christ and his Church.”[14] By making specific allusion to Christ at the very time that Othello and Desdemona are wed, Shakespeare ensures that we take note of the symbolism of marriage.

Two references to the Bible with regard to Desdemona confirm this allusive matrix. First, Brabantio, during Othello’s trial, describes Desdemona as “A maiden never bold; Of spirit so still and quiet that her motion Blushed at herself” (1.3.94-96), alluding to 1 Peter 3:4-5. This suggests that she is an ideal Christian woman. Shortly after this, as Othello offers his defense against Brababtio’s accusation, he describes Desdemona in language that recalls the Gospel story of Martha and Mary.

. . . This to hear

Would Desdemona seriously incline;

But still the house affairs would draw her thence,

Which ever as she could with haste dispatch

She’d come again, and with a greedy ear

Devour up my discourse; . . . (1.3.144-49)In these two allusions to Scripture, then, Shakespeare suggests that Desdemona is a woman of exemplary character, as if she were a combination of Mary and Martha.((Both of the references here are noted by Shaheen, who suggested that Shakespeare combines Martha and Mary into one and points out that nothing like this is found in Cinthio’s story. Shaheen, Op. Cit., p. 584.)) This also associates her with the story of Christ, reinforcing the parallel between Othello’s marriage to her with Christ’s to the church. Thus, to evoke Biblical associations with both Othello and Desdemona, Shakespeare modified Cinthio’s story to add allusions that connect the Biblical story of Jesus with his Othello and to suggest the relationship between Christ and the church. This gives a transcendent dimension to the domestic realities of the play and makes the story of Othello a story of “Everyman.” This qualifies as great tragedy because it is a retelling of the Fall of Man in the fall of Christ-like Othello.

Now using this symbolic framework, lets compare the play with the papacy of Pope Benedict XVI. Please stick with me, I promise all will become clear.

The Pope is the vicar of Christ. In the Catholic tradition, he is standing in for Christ on earth, to tend for his Bride, the Church.

Benedict XVI was elevated to the Papacy, to become the Bridegroom of the Church. Immediately he was beset by internal factions, furious as they did not get their Bridegroom elevated, and certain agents pretended to be Benedict’s close confidant, offering him advice, while secretly plotting against him. (Cough Cough Bertone, cough cough the man who awarded Jago the sculptor the pontifical medal for his bust of Benedict cough cough cough).

The play Othello begins with Rodrigo, a man in love with Desdemona and enraged that Othello has married Desdemona instead of him, scheming with Iago to destroy the marriage. Iago despises Othello because he promoted someone over him. They plot to end the marriage.

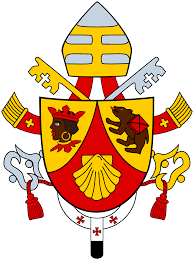

A quick reminder, Othello is famously a moor. And there is an odd little detail I should also add. Pope Benedict XVI’s coat of arms, his papal stemma, had an interesting heraldic feature that is seen as bit outdated. A feature only really seen today on the flags of Sardinia and Corsica.

The head of a moor. Popes are very often associated with their crests. So much so that in the famous Prophecies of Malachi, half of the prophetic statements are associated with features of the Popes coat of arms. These are things that are noticed.

By the end of the play, Benedic—erm I mean Othello— ends up realizing he has been manipulated by his good friend (who with his faction was secretly plotting against him) into doing the unthinkable. Killing his bride and then himself, voluntarily ending his marriage.

Could it be possible, that a theater kid around Pope Benedict, a duplicitous manipulator who fancied himself a Iago, decide to broadcast his plot through the thematic prism of the play? Did some Iago, a Iago dressed in red, a Prince of the Church, find a young sculptor, and promise him fame and fortune if he would play by a certain script? When did Jacopo Cardillo start going by Jago? Anyone with knowledge of the Renaissance knows that artists were primarily painting the requests of their patrons. It is not impossible that a modern artist is following the directions of his patrons, and simply hiding the fact.

The Catholic Church is an institution obsessed with ritual and symbolism. It stands to reason that high ranking members would be drawn to such things. Whenever I try and explain what I mean when I speak of ritualistic psychodrama or mass ritual, I bring up a passage from Algis Uždavinys’ book Orpheus and the Roots of Platonism. In this excerpt, he describes how in ancient Egypt the Pharonic priesthood communicated with the divine in cultic ritual.

What if we expanded this cultic communication to a wider scale, with even greater levels of symbolization. With some actors in this ritual play quite possibly not even being fully aware of their role.

When Jago the artist strips the bust of Benedict, it is a public display with several levels of symbolization. Jago the artist stripping the bust. Iago the cardinal stripping Benedict of his papacy. The Devil stripping Christ (whom the Pope is his vicar) of his bride.

Jago the artist is a proxy for his patron, the real Iago, the cardinal.

I am not what I am.

Iago the cardinal thought he was manipulating Benedict XVI into killing his bride Desdemona (the church) through his own symbolic suicide, his renunciation of the papacy. But if Andrea Cionci is correct, Benedict saw it coming. He outsmarted Iago, he never truly killed himself (resigned).

Through this framework, we may find another clue as to the strange addition of eyes into the finished bust of Benedict XVI. The first version had no eyes, it was blind. The second version had them included. In a famous line in the play, Othello is told:

"Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see. She has deceived her father, and may thee."

___________________

The rest of this article will be focused solely on more sinister aspects of Jago’s work.

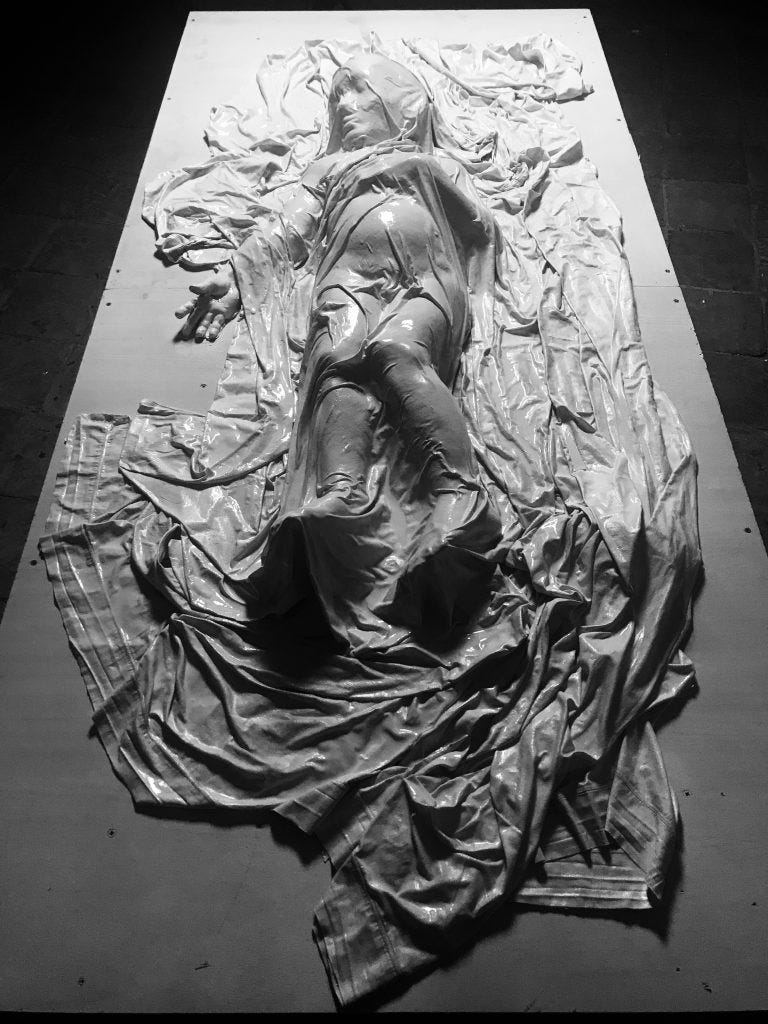

Benedict XVI would die on New Years Eve, 2022. In the months leading up to his death, Jago was busy hosting a strange exhibition.

He claims it was to represent a refugee, but this identification does not make much sense. It shows a withered man resembling a corpse. The first display of it was on a ship.

The next in Rome’s Olympic Stadium. This was in August 2022.

Finally, in October 2022, it reached Ponte Sant Angelo. In front of Castel Sant Angelo, which by the 16th century functioned as a fortress and residence for the Pope to stay in case the City was under siege. Across the bridge are angels holding the instruments of the Passion.

If you look carefully, you may notice a subtle likeness.

What appears to be a familiar tuff of hair emerging from a zucchetto.

Almost as if this statue was a representation of Benedicts looming death. Coming on a boat, and each month getting closer to Vatican City, until it was at his doorstep, on the very bridge most associated with the papacy. (Remember the etymology of Pontifex Maximus).

And but two months later, Benedict himself would die.

Was this the final commission from the real Iago to the sculptor? The final piece in this performative display?

Who is to say?

I will say this, the name of the piece was In Flagella Paratus Sum. I am ready for the whips. It is a reference to the inscription on one of the angel statues on the bridge, holding the whip that would scourge Christ before his crucifixion and death. And there is another layer, a reference to one of the last words of Othello in the play, before he kills himself.

“After Emilia reveals the truth about Iago and the handkerchief, Othello looks at the body of Desdemona and is so possessed by the image of his dead love that he feels it would be better to be in hell:

Whip me, ye devils,

From the possession of this heavenly sight!

Blow me about in winds! roast me in sulphur!

Wash me in steep-down gulfs of liquid fire!

O Desdemon! Desdemon! dead!

Is this how the real Iago hoped Benedict would feel in the end? As Othello? After realizing he had killed his bride? That his resignation, his suicide, had damned him?

That is one fucked up theater kid.

___________________

We will continue this in the second installment.