Discover more from Pope Head Post

I’d wager that many of my readers may find my claims outlandish, which is certainly understandable. In today’s world, the idea of an occult undercurrent bubbling sotto la superficie, haunting the shape of history, is deemed wholly ridiculous. Worse, it conjures up memories of the “Satanic Panic” and “right wing Qtards.” They would have us believe that Grimoires are no more dangerous than a Hasbro ouija board, fit for children and halloween parties.

For my claims to hold weight, that ecclesiastical symbolism is being intentionally inverted by darker forces, there must be historical precedent. The entirety of my analysis is predicated on the existence of fallen clergy, who openly engage with the occult, implicated in political intrigue and connected to the upper stratum of society.

A google search will not shed light on this issue.

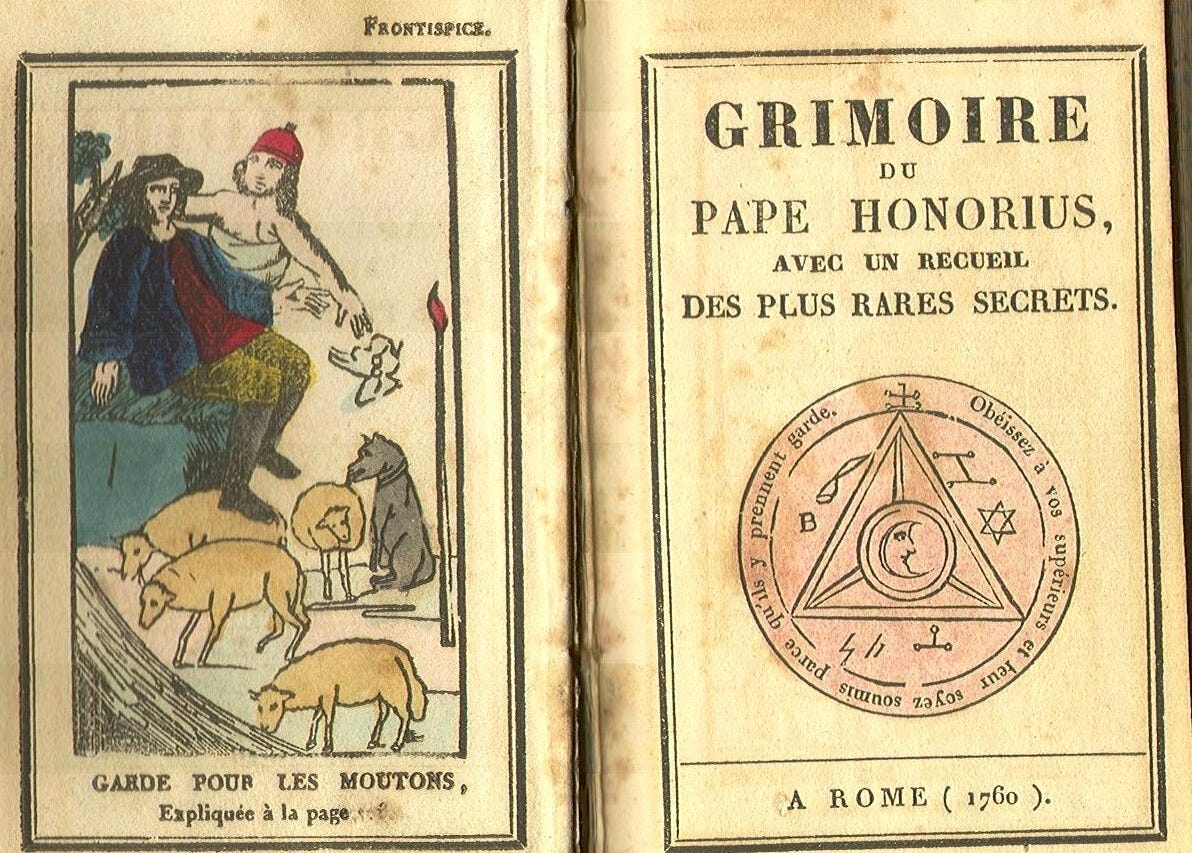

Clerical interest in the occult is nothing new. For much of the last millennium of western history, to be a scholar was to be a priest. The cloth attracted men of ambition, men of intelligence, and certainly more than a few men of questionable morals. For a parish priest or monastic scholar to come into contact with a grimoire would have undoubtably incited a morbid curiosity, or even lead to practical experimentation. In fact, we have records of Goetic spell books written for the exclusive usage of priests.

The Grimoire of Pope Honorius, spuriously attested to the eponymous Pontiff, was one such example.

This wasn’t a prank. These books weren’t 17th century shitposts. A printing press or scribe didn’t risk execution at the hands of the inquisition just to ‘have a laugh.’ This is before the days of bored schizos on /x/ recounting their imaginary encounter with a Wendigo. And if these tomes did not produce at least some tangible results, they would not be reproduced. This was a form of ancient technology.

Today we will discuss an extremely well documented and highly attested to event of the 17th century. It will serve as a microcosm for the darker forces that lurk about the fringes of human history (and in its center), and will simultaneously serve as a meditation on Baroque society and the nature of man. Today we will recount to you the plot to murder Pope Urban VIII, using the power of black magic. A plot involving high nobility, fallen priests, and goetia. An occult assassination attempt that shook the fabric of Roman society, but that did not come as a surprise. Baroque Rome was a time of intensity, of contradictions. A time of daily miracles and unfathomable bloodshed. A time of high art and lavish displays, and paroxysms of religious zeal. Where a normal day entailed your neighbor being beheaded in broad daylight, hours before a public apparition of the Virgin Mary.

Baroque Rome is a fantasy world in which I can escape, a unified spectacle, a theater, where lavish displays and Christian piety collapse into one. And in my coral colored palace of the past, I am granted glimpses of the future.

“Egyptian priests, using a drop of ink for a mirror, undertook to reflect on the past for the purpose of sharing revelations to their devotees in return for offerings that were immediately consecrated. It seems that past events were considered to be matters to reflect upon as well as being a source of revenue. It has long been said that history repeats itself and that the past is a mirror of the future… Ancient Egyptians believed that the past and future had such a relationship, and that the present mirrored both, a belief that is associated with the double house of life myth. When the Egyptian priests reflected on the past, perhaps they were endeavoring to ascertain the future. However, it was generally believed that the future was best seen in a drop of wine.”

_____________________

“

“

___________________

In the early 17th century, an Augustinian friar was forced to flee his native Palermo. Charged by the authorities with the abominable sin of witchcraft and necromancy, he fled to Spain. The skeptic may posit that his expulsion for practicing magic was simply a fabrication of the political nature, a bogus charge to slander a man with many enemies. But this was not the case, and after arriving in Spain, he was soon expelled for the same reason. Finally after sojourning in a host of regions, every time being expelled for engaging in the dark arts, he arrived back in his native Italy. He took up shop in a convent in Le Marche. Bernardo di Montalto once again gained a reputation for witchcraft.

This reputation attracted the attention of an Augustinian Prior by the name of Domenico Zancone. Zancone wanted help seducing a woman who had spurned his previous advances, and wondered if Bernardo di Montalto could assist in delivering some witchy solution. Bernardo’s advice involved constructing a wax doll to metaphysically pull at the woman’s heartstrings (or loin strings) via a specific ritual.

Enter a nobleman by the name of Gacinto Centini. Gacinto came from common stock and lineage, but by the blessings of chance or fortune, his uncle Felice had been made a Cardinal in 1611, instantly conferring noble status to his immediate family. Giacinto went from humble farmer to a Count with a wife from a wealthy family. An enviable position indeed. But the frailties of the human soul were painfully apparent in the young Giacinto, and his avarice and ambition had him craving a higher position, this undeserved gift of fate did not satisfy his appetite. He realized that if his uncle could ascend to the throne of Peter, the pinnacle of the church, he would be granted unparalleled privilege and power. That his dear uncle may raise him to the Red, as Cardinal-Padrone. But the only red he would inevitably wear would be that of his own blood, that which would mar his tunic in Campo de Fiori many years later.

Giacinto was growing impatient. He asked Domenico Zancone for a grimoire, in the hopes it may assist his own ambitions. Zancone eventually introduced Giacinto to Bernardo.

Bernardo conducted a magical operation at Giacintos behest, a divinatory reading of the future, to answer Giacintos burning question. “Would my uncle be Pope?” Bernardo, after consulting the stars, concluded that it would be so. The only problem now was that Urban VIII was still breathing.

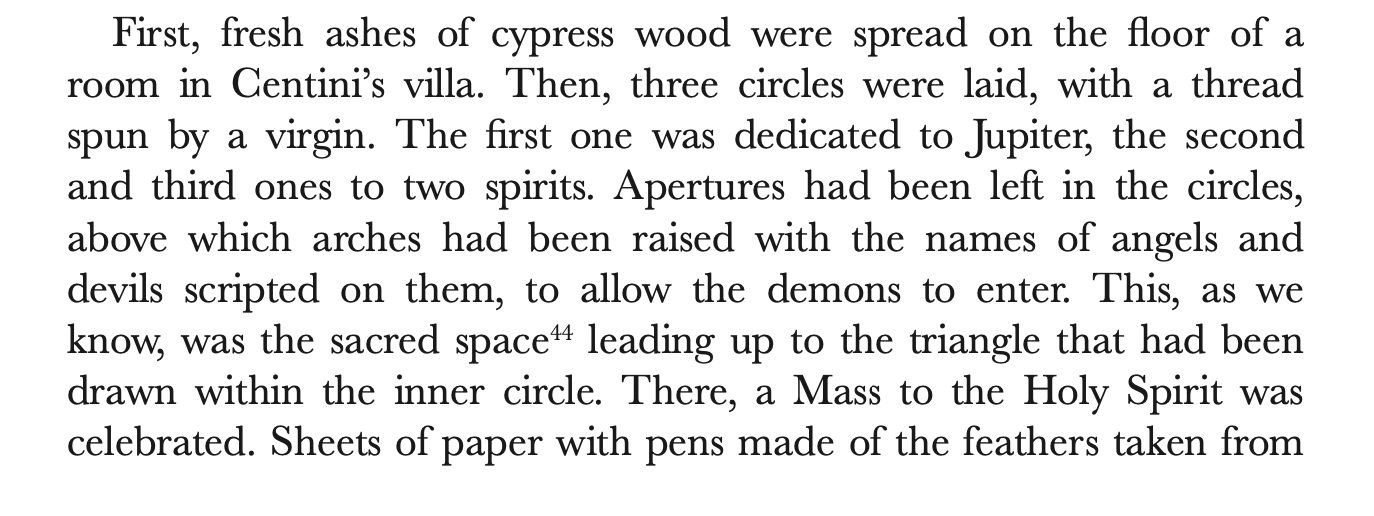

Bernardo suggested a magical operation to remedy the issue. The three of them got to work in executing the occult assassination. Here is a description of the ceremony below.

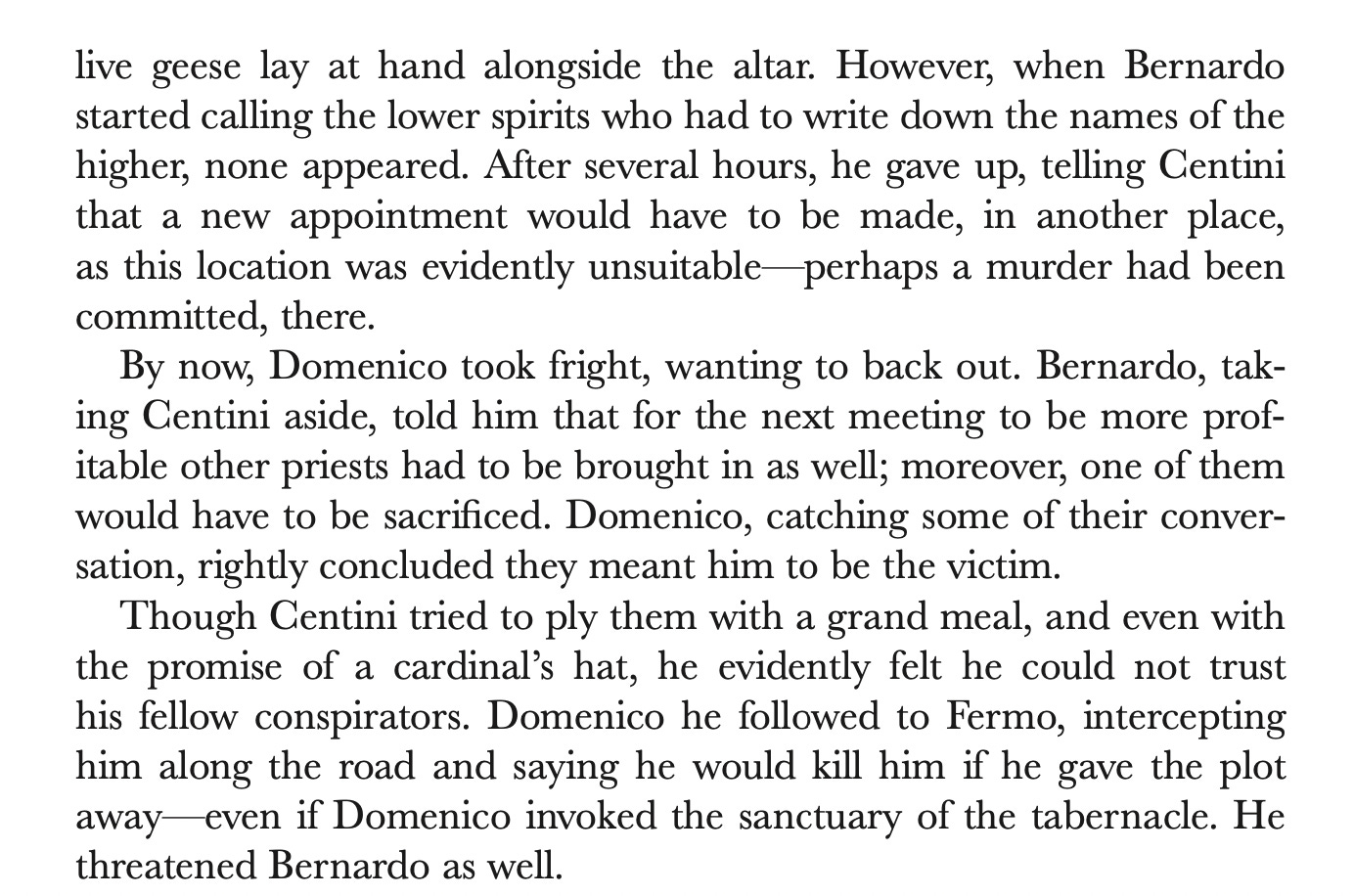

Thus begins our occult comedy of errors. The absurdity never undercutting the severity. As we shall see, the resulting attempts read as a Shakespearean comedy.

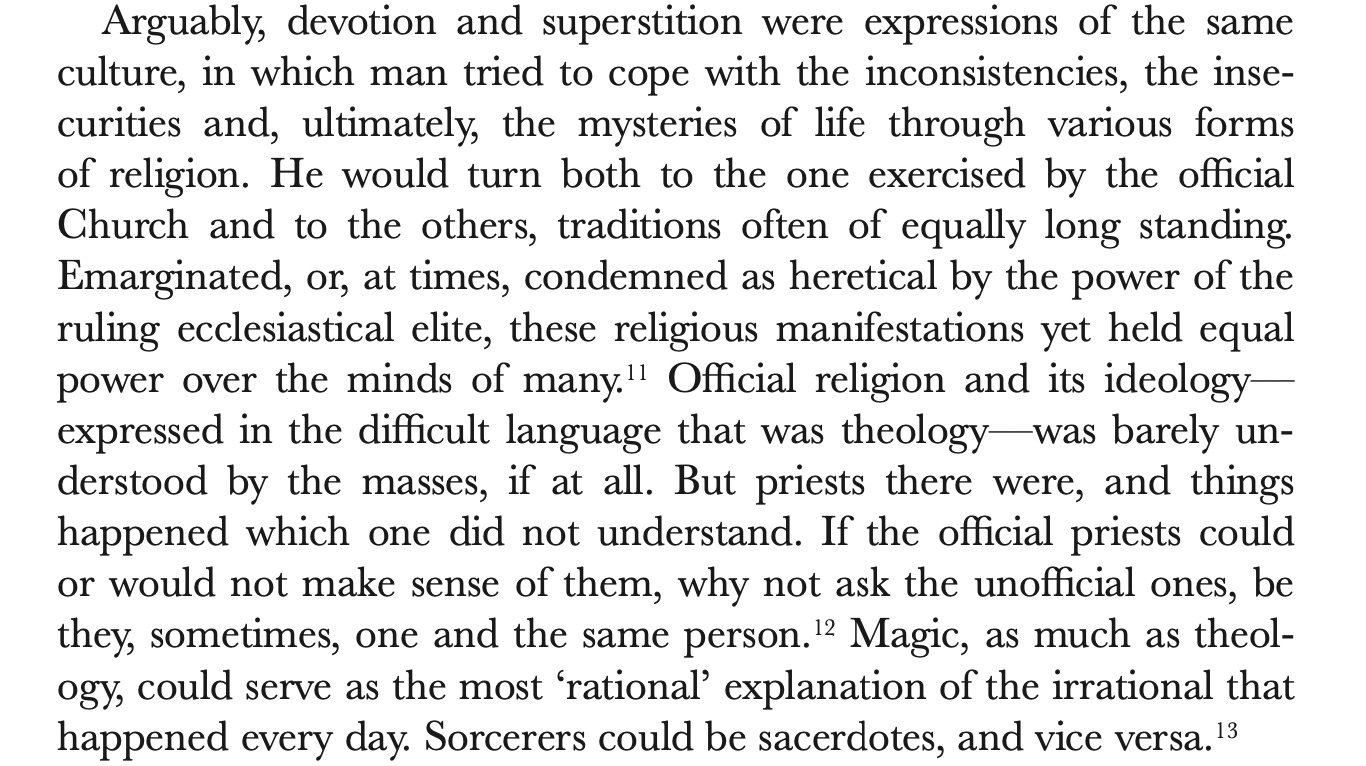

A quick note, notice the combination of “Catholic” liturgical ritual and goetic spell craft. This is important to understand if one wishes to get an accurate view of the nature of such things. This syncretism can manifest in various forms in various occult traditions. The works of Eliphas Levi attest to this. It’s why Husysmans remarked in La Bas “there can exist no mature satanism without the assistance of fallen clergy.”

And so our band of bumbling occultists scoured Abruzzo for a suitable location. Notably, in one location a spirit did indeed appear, on a kind of practice run they held with the statue of an innocent woman. The women supposedly died after.

For the next go at the ritual, Bernardo demanded no less than seven priests to be in attendance. However, at this point things began to unravel, and in the following months all the conspirators were apprehended.

I am going to quote one more block of text verbatim, as I believe it will serve as an enlightening window into Baroque society.

This is a perfect window into the distinctly Christian and distinctly pre-modern view of execution, something completely alien and ghastly to the majority of us today. The crowd kissing the instruments of execution as if they were holy relics, keenly aware of the redemptive power death possessed. Centini was to lose his head, but save his soul. In the Baroque mind, it wasn’t this life that mattered, but the next. If the hangman’s axe could deliver a soul to heaven, it was an instrument of salvation and not brutality. The modern man abhors the death penalty but wishes for the worst torments to befall the criminal while he finishes his miserable existence in a cell, believing that no torment exists after the end. While the Christian of old viewed execution as a necessity, but prayed for the soul’s ascension to heaven upon their demise.

Huysmans in a stroke of literary genius meditated on this medieval vs modern distinction in La Bas, when he described how the crowd reacted to the execution of the heinous murderer Gilles de Rais.

_____________________

The Rome of Pope Urban VIII was filled with such stories. Fallen priests, occult networks, etc etc. These were not paranormal bed time stories to chill the blood, but a daily reality in a world full of equal parts barbarity and divinity.

We will delve deeper into the holy sediment of Baroque Rome in a later article.

Edit:

Forgot to list my sources.

Power and Religion in Baroque Rome - PETER RIETBERGEN

La Bas - Joris Karl Huysmans

Subscribe to Pope Head Post

Papal history and deep topography.

Um. Ouija boards are dangerous even when they are toys from Hasbro. I know I sound ridiculous (I can own that) but they are.

Nice article but I am curious about the source of the quotes. Would love if you included a works cited.