Discover more from Pope Head Post

There exists certain men, certain modern mystics, who are endowed with a prophetic vision, a spectral inertia, which manifests within the contours of the artistic impulse. These visionaries are capable of a “second sight,” a clairvoyance that allows them to “scoprire il dèmone in ogni cosa,” to perceive objects in their hidden form. And so amid this strange and secular age, these seers stumble upon the oracular impulse, rediscovering it as if by mistake, relearning some art that lay dormant in the spiritual vapors of the blood.

Many early authors of “weird fiction” seemed to possess this ability. Robert W Chambers, HP Lovecraft, and Jorge Luis Borges all stand out in this respect. Chambers in “The King in Yellow” (1985) predicted the US entering and winning a war with Germany, the career field of Public Relations, and the invention and acceptance of voluntary euthanasia chambers. Borges anticipated the internet. In the creation of pure fiction, these eccentric artists seemed to pierce the veil of temporality, receiving an imprint of what was to come. But our focus today is not on an author, but a painter. And such a gift is far more rare in men limited to crafting paintings and not stories. That painter is Giorgio de Chirico.

On a purely aesthetic level, what distinguished Giorgio de Chirico was his ability to haunt without being overtly grotesque. To get under your skin with a surgical subtlety. A nightmare without gore, he crafted strange constellations using the alchemy of distance and proportion to unsettle and shock the spirit. The uncanny phantasms he conjured were an extension of a deeper gift, a mystic gift, an ability to enter into the faery realm of unbegotten forms.

The imbecile man, the non-metaphysic, is instinctively led towards the appearance of mass and height, towards a kind of architectural wagnerism. Affair of innocence; they are men who do not know the terrible lines and angles; they are worn versus the infinite and it is here that their limited psyche is revealed [...]. However, we who know the signs of the metaphysical alphabet know which joys and pains are enclosed within a portico, the corner of a road or even in a room, on the surface of a table, between the sides of a box.

The limits of these signs constitute for us a kind of moral and aesthetic code of representations and moreover, we, with clairvoyance, construct in painting a new metaphysical psychology of things.

Who can deny, the troubling connection between perspective and metaphysics?

-Giorgio de Chirico

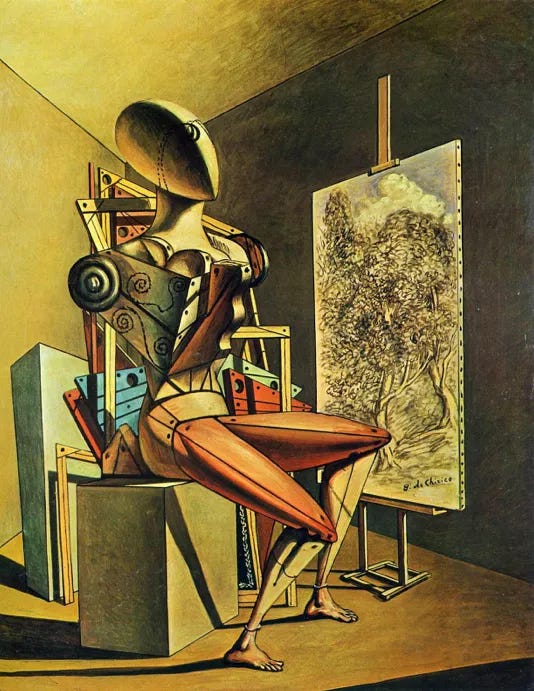

“De Chirico developed the motif of the mannequin in conjunction with Apollinaire and Savinio. The human substitute without face or voice is blind like the seers of antiquity and equally gifted with the power of prophecy. The mannequin is the alter ego of the artist: the blackboard records stations along De Chirico’s artistic journey” (p. 40). “The mannequin, in conclusion, represents the achieved figure of his personality as it “becomes a modern formulation of the blind seer of antiquity, a figure with visionary powers. At the same time, it offers a graphic analogy with the increasing loneliness and alienation of modern man, the dissonance of human existence”

-Magdalena Holzhey

Nicola and Podoll points out: “He considered his power of access to this particular state of mind as the very essence of his artistic creativity, at least in the metaphysical period.”

Furthermore, what to think of the fact that “he claimed to have revelations, premonitory and clairvoyant dreams, to see inside objects as if he had an X-ray view? Or finally when he attributed himself very special, if not even paranormal, powers, such as becoming, but only sometimes, phosphorescent?”

De Chirico himself, highlights: “For example, I am phosphorescent. I’m not kidding ... I see my hand in the dark. Moreover, the more time passes, the more I realise that I am an extraordinary man” His words leave no shadow of a doubt on the way he perceived himself and on the powers he thought to possess, powers among the most disparate.

In conclusion, according to De Chirico, the world can be perceived according to two specific and antithetical aspects, “a usual one, which we almost always see and which men generally see and the other, the spectral or metaphysical, which can only be seen by rare individuals in moments of clairvoyance and metaphysical abstraction.”

- Lucio Giuliodori

It is not my intention today to give an overview of de Chirico’s life and work, and I think the above quotations give an adequate introduction (or initiation) into the eerie oracular quality humming within the echoes of his oeuvre. There are many strangely prophetic features of various pieces of his that have been commented on in the past. For one, the painting he did of Guillaume Apollinaire in 1914, featured a bizarre deformity on his forehead. Three years later, Apollinaire would be severely wounded in WW1, after taking a bit of shrapnel right to the cranium, in the same area where the aberration had been placed by de Chirico.

Another one of his artistic prophecies seemed to come to pass a hundred years after it first found form on canvas. His empty piazzas. With Covid 19, all of Italy became a de Chirico painting. I will never forget it, a couple weeks into the pandemic, walking into Trastevere and seeing all of Piazza Trillussa empty and silent, bathing in the nostalgic glow of a late Roman afternoon.

And I can assure you, during that period, time became altered in uncanny ways.

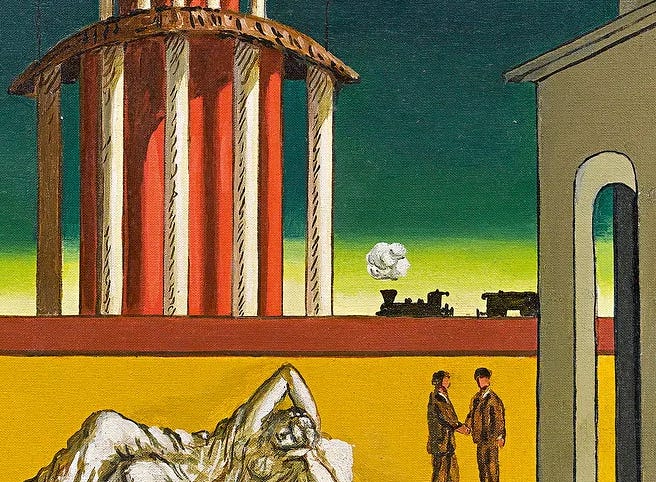

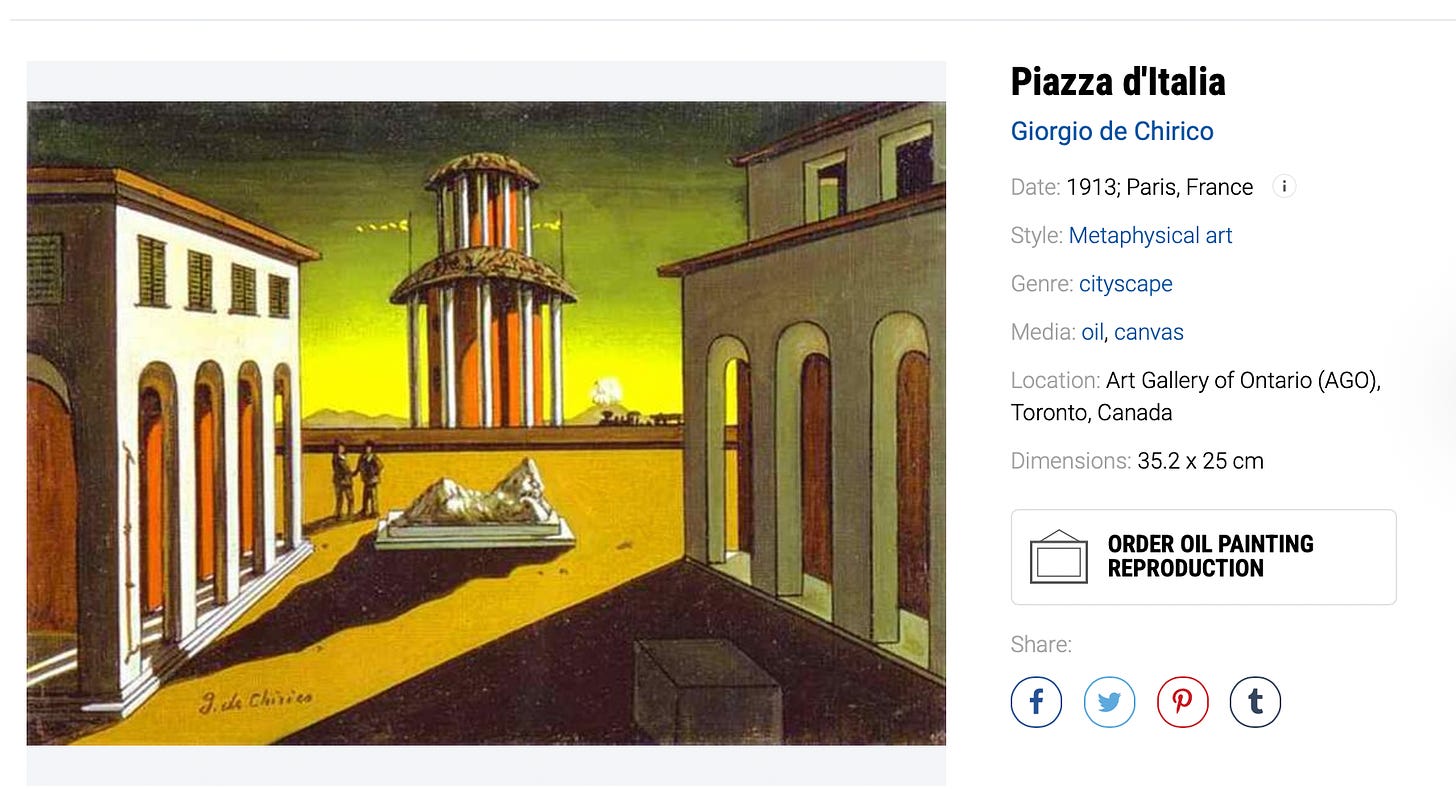

However, this article will be focused on one particular image of his, the first that drew me in and under his spell. A painting coiled in riddles, a dreamscape boiling over with sinister themes. A painting he recreated countless times. De Chirico’s Piazza d’Italia.

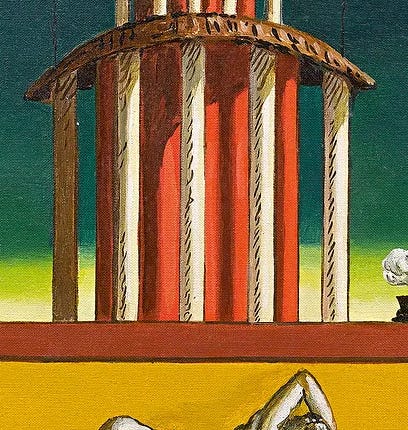

Why did this variation first capture my attention? It was that familiar form lurking in the background. An unmistakable shape. The Temple of Hercules Victor in the Forum Boarium. (De Chirico spent much time in Rome, and many of his paintings were at least partly inspired by the eternal cities angles).

But in de Chirico’s day, it is quite possible he did not even recognize its Herculean dedication. (at least, not consciously). Even modern commentators often confuse it with the Temple of Vesta, which simply makes everything that comes next even more profound. The identification of de Chirico’s painted tower and the aforementioned structure is common among art historians, but even they tend to misidentify it.

-James Thrall Soby

Pictured below is the actual Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum, tell me, which temple looks closer to de Chirico’s tower?

What is extraordinary is that when one begins to connect the various reference points of this particular dreamscape, a strange and powerful internal logic presents itself, one that hints at the continuity of the artist’s subconscious and the very flows of reality.

The center of the painting consists of two main subjects. The tower that resembles the temple of Hercules Victor and the statue of Ariadne, who was a common subject of de Chirico’s work. Ariadne “was a Cretan princess and the daughter of King Minos of Crete. There are different variations of Ariadne's myth, but she is known for helping Theseus escape the Minotaur and being abandoned by him on the island of Naxos.” I believe that through a stroke of subconscious genius (although magical is a more fitting word), he aligned these two particular structures, to form an astonishing constellation of symbolism. Let us begin to peel back the layers.

If we are to equate the tower with the temple of Hercules, then the piazza itself would be in one sense within the forum boarium. Remember, in the work of de Chirico, temporality is twisted, diverse locations collapse into a single point, a single unbegotten locus. By placing Ariadne in the forum boarium, a startling connection begins to manifest.

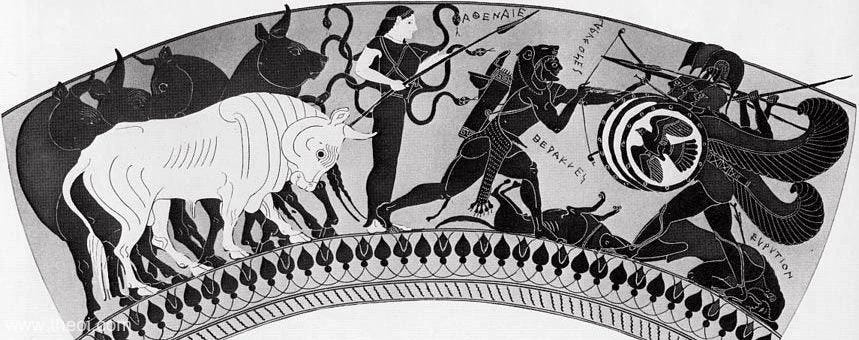

Ariadne, as stated earlier, is most strongly associated with the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. There are several variations of the myth, and I will provide a brief synopsis to refresh your memory. King Minos of Crete’s oldest son Androgeus was murdered in Athens while participating in the Panatheniac games by envious competitors. The King sends the Cretan fleet to punish the Athenians, and eventually “His retribution was to stipulate that at the end of every Great Year, which occurred after every seven cycles on the solar calendar, the seven most courageous youths and the seven most beautiful maidens were to board a boat and be sent as tribute to Crete, never to be seen again.” (Another telling of the myth explains that the oracle advised the sacrifice). The seven pairs would then be devoured by the “minotaur a half-man, half-bull monster that lived in the Labyrinth created by Daedalus.” Eventually, the great hero Theseus volunteers as one of the offerings to slay the minotaur. When he arrives on the island, the King’s daughter Adriadne falls in love with Theseus and assists him in slaying the beast.

If you were paying attention to the last article, you would immediately pick up on the first sinister connection between the Forum Boarium and the story of Ariadne. Human sacrifice. And not just any human sacrifice, but the sacrifice of male and female pairs due to martial threat (and at the oracle’s behest). In the Athenian case, the pairs were offered up to appease the Cretans, and in the Roman Forum Boariums case, the sacrifice was done for assistance in the Punic War.

Meanwhile, in obedience to the Books of Destiny, some strange and unusual sacrifices were made, human sacrifices amongst them. [6] A Gaulish man and a Gaulish woman and a Greek man and a Greek woman were buried alive under the Forum Boarium. They were lowered into a stone vault, which had on a previous occasion also been polluted by human victims, a practice most repulsive to Roman feelings.

-Livy

This oracular sacrifice binding both locations imbues the scene with a lurking sense of malevolence, a horror churning in the recesses of shadow. There appears even to be a strange numerical coherence within the scene, but this is a mystery I will leave unsaid.

What were the COVID lockdowns if not a bizarre case of human sacrifice, the sacrifice of a nation’s youth to supplicate some foreign horror? A sacrifice decreed by a new breed of technocratic oracle. Immolated upon the golden hue of an empty piazza. The Piazza d'Italia. The weight of de Chirico’s prophetic inertia grows heavier with each passing moment of contemplation. But the most astonishing revelation is yet to come.

Let us continue to explore the possible associations between Ariadne and the tower. Turn your attention again to the tower in the scene. While it looks structurally identical to the Temple of Hercules Victor (besides of course for the addition of the second set of columns above) the color scheme is wrong. And yet, quite incredibly, the color scheme resonates with an aspect of Ariadne’s myth. The overall effect is almost identical to the hues on The Palace of Minos in Crete.

Almost identical shades of red, yellow, and white. What extraordinary artistic power! The two forms are seamlessly weaved into one, both the temple of Hercules and the palace of Minos! I do not believe this was consciously intentional, I believe that the visionary artist had these mythical forms assemble themselves within his soul, swelling up in a stroke of creative fantasy, blooming into this dreamscape.

More parallels continue to emerge. Recall the relationship between Hercules and Ariadne’s would-be lover Theseus. It is Heracles who goes down into Hades to free Theseus, which adds a Cthonic terror to the painting, the two heroes submerged in the netherworld as Ariadne lies abandoned, comforted only by that tower, that temple to Hercules with the color scheme of that palace she left to abscond with Theseus. And now she sits abandoned in Naxos, and yet, it is simultaneously Crete and Rome, time and place pooling into one cerebral vision! This is the power and force of de Chirico. And so she waits, waits for Dionysus and apotheosis, an ascension that will never come in this eternal afternoon of de Chirico.

With this framing in mind, the train takes on a new significance.

There are no train tracks behind the temple of Hercules Victor in Rome, but there is another avenue of transportation. The Tiber River and the oldest port in Rome.

In such a perspective, the train transforms into a ship, leaving port, the ship of Theseus, as Ariadne lies abandoned. Or the ship of Hercules as leaves for his next labor. This fluid stitching of multiple mythological subjects into a handful of forms is nothing short of masterful.

In fact, in his 1955 version of the scene, the train is replaced by a ship.

It is time for our next symbol that haunts both the statue of Ariadne and the tower of Hercules Victor. That of the bull.

As discussed in the last article, The Forum Boarium is the location in which Hercules was said to have come to Rome during his 10th labor, when Cacus stole the cattle of Geryon from him.

And of course, Ariadne is associated with Theseus’ slaying of the Minotaur, a monster half man and half bull. It is here, that I think the most startling prophecy was made by de Chirico, why he chose Ariadne for this scene, to reinforce the bullish quality infused in the Genius Loci.

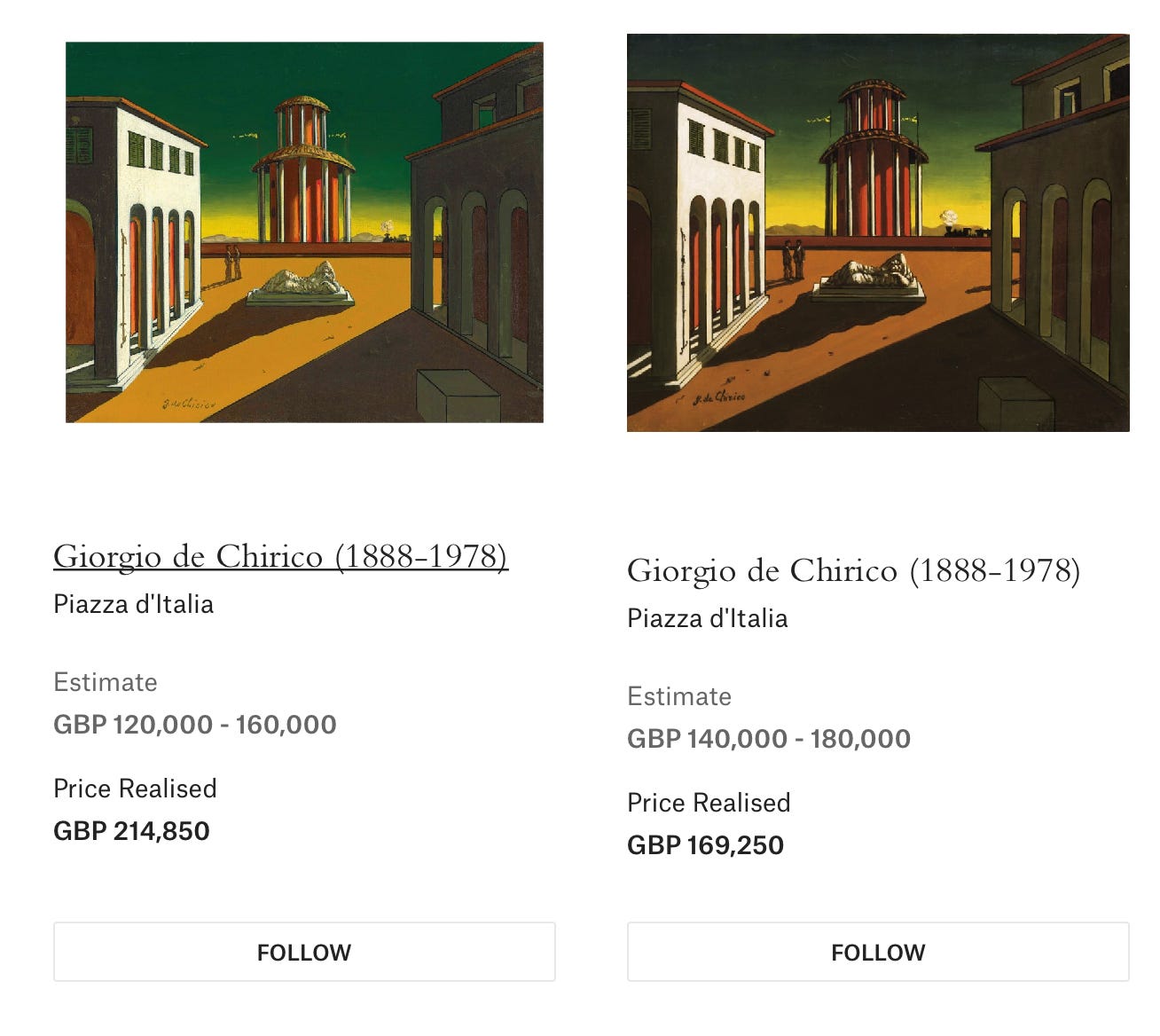

Now before continuing, it is important to note that in de Chirico’s later years, he painted hundreds of variations of his Ariadne in this liminal piazza. But the variation he repeated the most was this one, with the Herculean temple with the colors of Knossos. Obsessively, near maniacally. He was called a hack for these near-endless “facsimiles.” But I believe something different was occurring. It was this scene, this compilation of disparate phantasms that was the most perfect, the one he had to repeat. One look at the Christie’s auction website and you will see just how many variations there are.

The original variation of the painting was supposedly done in 1913.

If this is truly the case, then I believe we have his most stunning example of prophecy.

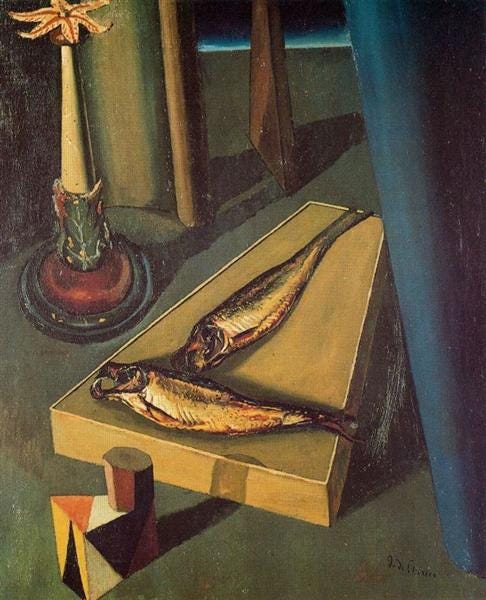

And the secret lies cubic in the bottom right.

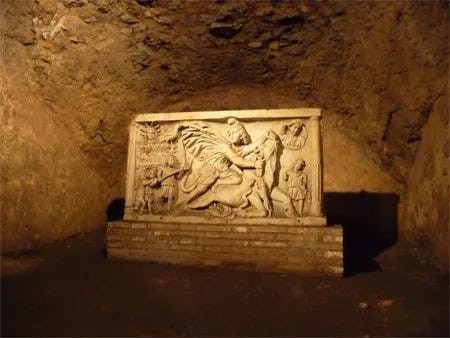

If this was indeed first painted in 1913, then it predates the discovery that occurred in the 30s under the Forum Boarium. A discovery thematically linked to the bull-killing motif that de Chirico showcases by alluding to both the Temple of Hercules Victor (the cattle of Geryon and his subsequent sacrifice) and Ariadne (Theseus slaying the minotaur). The Mithraeum underneath the Forum Boarium.

He claimed to have revelations, premonitory and clairvoyant dreams, to see inside objects as if he had an X-ray view.

Even more stunning, if we were to align ourselves in the Forum Boarium, gazing out at the Temple of Hercules Victor, the mithraeums Tarouctony altar would be almost directly under the grey cube he has floating above the surface.

(The topmost circle next to the blue tiber is Hercules Victor, the orange rectangle the Mithraeum).

I am convinced that de Chirico’s spectral sight gazed under the haunted topography to recover the outline of that object, retrieving it from the ground in this display of mystic archaeology.

In some variations of the painting, the cube elongates, more suitably matching the form of the altar.

The cube is always cast in shadow, subterranean, cthonic.

The obsession on these objects, these themes, these myths, in this single piazza, in this arrangement, I believe this was a stroke of genius unlike anything I have seen before.

I could continue, but I believe that is enough for now.

When I close my eyes my vision is even more powerful.

-de Chirico

Subscribe to Pope Head Post

Papal history and deep topography.